The Great Annealing

Cross-posted as always from Putanumonit.

Michael Johnson of the Qualia Research Institute wrote an overview of the theory of neural annealing.

The metaphor comes from metalsmithing. A newly forged sword is ductile and tough. Then you bash the outgroup on the head with it and every bash creates a stress point in the sword: some part is bent, or stretched, or slightly cracked. Even elastic metal can’t spring back perfectly to it’s original shape, and the sword becomes brittle and stiff. To restore it, you heat the metal to the point where its microstructure breaks down, then let it slowly cool and crystallize into stable unstressed patterns again.

Johnson, building on the work of Robin Carhart-Harris and others, proposes that the same process applies to brains. In the predictive processing paradigm, the brain starts a cycle from a stable state: neural activity is low-entropy and proceeds in fixed patterns. From the inside, this feels like confidence in your models of the world, and consistent affect in your reaction to things.

As more input comes in, the brain accumulates stress in the form of prediction errors. This manifests as confusion, anxiety, or unease: a person who reacted unexpectedly to something you said, news that upset you, an action that failed to achieve it’s intended consequences.

An ideal Bayesian brain would immediately update all of its model in light of every new bit of information, but our brains cannot physiologically do that. The stress of prediction error accumulates in the form of electrical energy in particular neural circuits, but can’t propagate everywhere (or even reach consciousness) until it crosses a particular threshold of excitation. Your conscious and unconscious models of reality live in silos with their own accumulated errors, separated from the rest of the brain by potential energy barriers (Scott Alexander calls them mental mountains).

To update, your brain needs to heat up, to build up too much energy at once to route through the habitual circuits of thought. Meditation and psychedelics are powerful tools for achieving that, but anything that fills your brain with new and unusual inputs can do the trick like a retreat into the woods or “mindblowing” sex. From the inside, a brain pumped full of entropy feels like a trip: unusual and novel thoughts without strong affect, creative excitement, or nothing at all if your mind is too chaotic to make any sense of it at all.

Once past a critical point, the mental mountains flatten out and all the modules of the brain can “talk to each other” and update at once. They can settle into a new equilibrium that would globally minimize the prediction errors accumulated so far and those expected in the future. This feels like insight or enlightenment, depending on the magnitude of the update.

Curing Jealousy

That was the theory, but I’ve had some powerful first hand experience with the process as well.

When I first began experimenting with open relationships, I didn’t think I was someone particularly immune to romantic or sexual jealousy. My partner at the time and I adopted a don’t-ask-don’t-tell policy. We treated jealousy as something to be circumvented, an ultimately useful emotion that needs to be suppressed in some novel contexts, similar to anger or fear. Even famous polyamory advocates like Geoffrey Miller carefully tiptoe around jealousy and distract themselves with utilitarianism and TV.

But as I read more books about evolutionary psychology, especially those by Geoffrey Miller himself, I began to question the utility of jealousy altogether in my life. Jealousy served the genes of my ancestors who needed to secure reproductive and resource exclusivity, considerations that aren’t relevant in 2020 and for my actual well-being.

The two models of jealousy inhabited my brain simultaneously — the evolved instinct to feel it, and the conscious idea that I’d be happier without it. Both models were accumulating error signals: the latter every time my wife went out on a date and I felt anxious and jealous, the former every time she came back happy to see me again and not pregnant. I lived with this internal conflict for the seven years since my first open relationship.

And then, I went on a retreat in the woods with friends. I meditated, had sex, and took psychedelics. With my brain as full of entropy as it’s ever been, I saw my wife cuddling with a male friend, both of them smiling at me. And I realized that the usual pang of jealousy that I expected to feel was completely gone, released like a muscle knot under massage.

I tried to summon the pro- and anti-jealousy parts of mind to hash their differences out in an internal double crux, but I was past that point already. Only the unjealous part showed up. I spent seven years contemplating jealousy and seven hours neural annealing, and by the end of it the jealousy was gone and remained gone.

Societal Annealing

It’s an irresistible temptation for anyone writing about neural annealing to apply the same model to society, particularly those coming from the view of an individual brain as comprising a society of multiple agents. Johnson writes about “social annealing” that happens in a shared context of religious service or sporting event. Carhart-Harris and Friston talk about psychedelics destabilizing social order and discomfiting the ruling elite in the same way they shake up the dominant thought patterns ruling the rigid brain.

The model, broadly speaking, is the same. Individuals in a society have their own worldviews and theories of reality, making their own individual predictions (implicit or explicit) and accumulating successes and errors. But in the normal course of things, good ideas don’t propagate and bad ideas aren’t dislodged very rapidly.

The world runs its course, people go to work and drink beer and watch TV regardless of the wrongness of prevailing ideologies. Almost everyone’s lives is governed not by physical reality but by the social reality around them, and unlike physical reality which is one, there can be as many coexisting social realities as social groups willing to courteously ignore each other.

In our brains, conscious awareness is the central stage on which mental agents can broadcast their models to the mind at large. Communication between mental modules occurs outside of awareness as well, but in a much more limited capacity. In society, the spread and proliferation of ideas is controlled and gated by central sensemaking institutions: the government and mass media. In a world not constrained by physical reality, these institutions can spin narratives full of errors and contradictions that go unnoticed.

But once in a while, physical reality grabs the world by the shoulders and gives it a hard shake.

In social-reality times, government can make bad policy, schools can teach bad ideas, newspapers can print nonsense, and they would not be found out for many years if at all. In an exponentially growing pandemic, bad policy and fake news get found out within days if not hours. Ideas that held center stage through sheer inertia and suppression get swept away by the tide, and smart ideas that were locked in a dark corner can spread and propagate at the speed of Twitter.

Government

No matter what happens in the news, a predictable consequence is political ideologists of all stripes will claim that the latest thing is proof of their wisdom courage and a complete refutation of their opponents. Progressives and conservatives, statists and liberatarians, are equally convinced that COVID validates their ideology and supports their pet policy prescriptions.

But I think that more and more people are realizing that political ideology has very little to do with how the state is governed. Political parties are merely coalitions of convenience, and the response of elected officials has nothing to do with their team colors and everything to do with their personality and circumstance.

A Republican president just signed America’s largest ever welfare bill, approved by a Republican senate. Their Democrat colleagues supported the travel restrictions and border closures. The governor of New York is deservedly getting praise for his decisive and informed action while the governor of Nevada is deservedly getting shit for banning doctors from prescribing hydroxychloroquine — they are both “moderate Democrats”, and that fact has zero bearing on their policy decisions.

The same is true on a global scale. Taiwan’s response has been exemplary and Spain’s abysmal; they are both democracies. Vietnam’s single party has managed to contain the disease so far while Iran’s single party is digging mass graves. Elected and unelected rulers are responding to the virus according to their whims, personal interests, whatever advice they may or may not be receiving, and circumstances that are mostly outside their control.

I hope that this will mark a reversal in partisan polarization, and a marginalization of partisans who continue to twist everything into their pet causes. Inshallah we shall see an abatement of the culture wars as the nature of the crisis beclowns identity politics on both the right and the left. But some people have been making a living stoking the culture war flames, and I don’t think they’re going to adjust well to a world of physical reality.

Media

While political ideology seems to matter little in how governments respond to a real crisis, the response by many media outlets showed that they contain little else.

Opinions of a given media outlet usually fall into two camps:

They are good people who tell the truth.

They are bad people who lie for personal gain.

This was my default implicit model — I thought of the truth I would print if I was a journalist, and attributed the falsehoods I saw in print to dishonesty.

In early February, when “prestige media” were churning out daily misinformation about the virus, Mason Hartman attributed their behavior to camp #2. I noticed that I was confused: wouldn’t the personal gain come to the alarmists who get lucky? We remember the people who predicted the 2008 financial crisis that happened; we don’t remember who predicted the crises of 2010, 2011, 2012 etc that didn’t.

But then author Tucker Max responded:

At first, I thought this was just snark, or a too-enthusiastic application of Hanlon’s Razor. I know a few journalists, and they are intelligent and curious people. What are the chances that I just happened to meet the outliers of the profession?

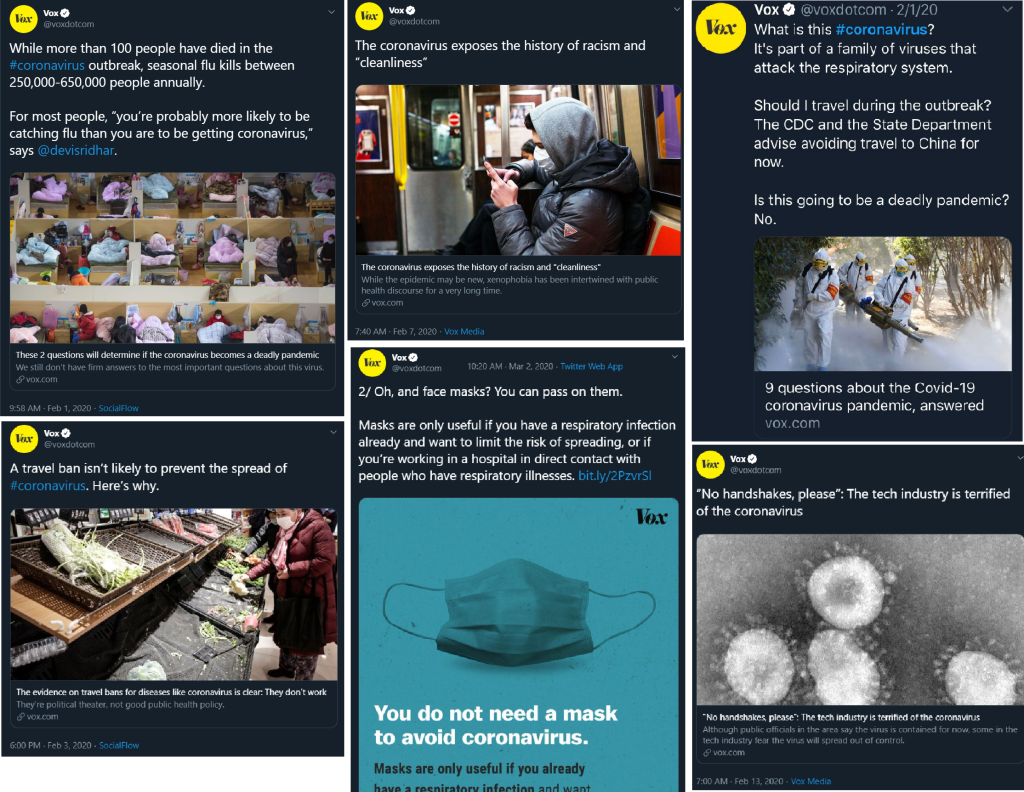

But the journalists kept writing, and Tucker’s tweet loomed larger with every article. Here’s a selection from just one outlet, Vox Media:

It won’t be a pandemic, the flu is worse, travel bans don’t work, masks don’t work, keep shaking hands, only racists are scared — all of these were reckless on the day they were written and proven false within mere days of publication. Nobody who is bending the truth for personal gain would write these articles. They were written by people who don’t know what truth is, who lost sight of the fact that reality exists and will pass judgment on their articles based on physical outcomes and not pure intentions.

They were written by people who don’t have the intelligence and scientific literacy to comprehend the mathematics of exponential growth, the physics of droplets in the air and on fabric, the difference between a study failing to show significance for an intervention because of a small sample size and a study “disproving” its effectiveness. These “explainer” articles are simply pattern-matching whatever news was printed elsewhere into a small set of affect-laden narrative templates: orange man – bad, big government – good, Silicon Valley – bad. (Most major media outlets have stumbled onto at least a few people who start from truth-seeking and not from narrative matching. I wonder how these writers are feeling about their “colleagues”.)

Most of these articles are neither truth nor lies, they have practically no information content aside from a few cherry-picked numbers floating free of context. You cannot learn anything by either taking Vox at face value or by flipping the affective sign on what they write. You cannot reverse stupidity to produce intelligence, which is another thing that a Vox correspondent is too stupid to understand.

Novel Sensemaking

Coronavirus has broken sensemaking for a large chunk of society. Some people interpreted events outside their immediate lives through a lens of partisan ideology, but partisan ideology turned out to be little relevant to the crisis. Some people relied on explainer media, but explainer media turned out to do little more than dress up partisan ideology in prettier language. Some people ignored world events completely, but now world events are making their way into your city, your job, into your lungs.

And this is the blessing of the COVID disruption — it’s an opportunity to learn new ways of making sense of the world. We should do it the same way our brains do it, by seeing which models make correct predictions and which ones go wrong. The novelty of the situation and the speed of unfolding events have tightened the feedback loops between our beliefs and reality, and the internet allows us to update together without relying on central authorities.

This doesn’t apply just to the virus itself. People are unlearning old ways of looking at education (was it just daycare all along?), the markets (aren’t they supposed to be efficient?), and the actual economy (why can the US make space rockets but not paper masks?) People are learning new things about their families, friends, roommates, and landlords.

If you’re feeling anxious and overwhelmed, that is a sign that the annealing has started. Old useless patterns have broken, entropy has replaced the semblance of order. But don’t hide away from the confusion, use it to build new ways of understanding, alone and with people you trust.

Make predictions and track them, and make a note of when you were right and wrong. Track the implicit predictions made by others, and whether they admit their mistakes or refuse to update. Make beliefs pay rent.

Give the absurdity heuristic a rest — the world is absurd. Downgrade credentials and titles, they are indicators of social reality. Recognize people who show tangible results, those come from physical reality.

And finally: meditate, have sex, work out, do drugs, whatever is available to you. Don’t escape completely into Netflix and video games, artificial worlds designed by clever writers to be easily made sense of in predictable ways. Absorb information and let your brain anneal, then spread the word to others. The world is not any stranger today than it was a month ago. Since the beginning not one unusual thing has ever happened. It is only our minds that fell behind. Now is the time to catch up.

As a follow up on the media angle, here’s something I posted on my Facebook:

We’re going to see a lot of research on hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin (HC&A), among other drugs, coming out in the next few weeks from around the world. HC&A is already the standard of care in several countries, in part because the drugs are cheap and widely available and in part because early results are promising. The combined evidence of these studies may show that other treatments are better as a first choice, or that HC&A is better, or that it depends on the particular characteristics of each patient. It’s always going to be complicated.

What the studies will never be able to do is *prove* that HC&A cures COVID since we already know that nothing works 100% for it. There is too much variance in how patients are selected for each study, how they’re treated, how outcomes are measured, and how an individual responds. There’s never one big indisputable hammer in small-N drug research, and there are always outlier results for people to cherry-pick one way or another. However, enough Bayesian evidence could mount that taking 600 mg of hydroxychloroquine at home at the first onset of symptoms or a positive test is better than chicken soup or going to an overcrowded hospital, all else being equal [1].

And if that happens, there is little doubt in my mind that mainstream media will fight for weeks against admitting that it is the case. They will hide behind “it’s not proven” and “more research is needed” and “but the FDA”. Facebook will be along for the denial ride claiming they “fight unofficial misinformation”, which is anything that’s not coming from the WHO (which is currently telling people not to wear masks). Many politicians will fight to suppress this information as well, especially if Trump starts gloating over some particularly poor pro-HC&A study and saying that he called it. Trump is an idiot, but reversed stupidity is not intelligence.

So, please don’t fall prey to Gell-Mann amnesia. The same people who bullshitted you about “it’s just the flu” and about closing borders and about masks would 100% keep bullshitting you about drugs. Journalists aren’t smart enough to understand cumulative research evidence, and organizations like WHO and FDA have institutional incentives that will force them to react two months and thousands of corpses too late. You have to learn how to read medical studies yourself, or follow people who can and who aren’t compromised by working in media or politics. The lives of your loved ones are at stake.

[1] I will not disclose here whether I think that’s already the case for two reasons. First, I don’t want Facebook to remove this post for giving unsolicited medical advice, so I’m only giving information consumption advice. Second, I am not the authority you should be listening to. It’s better that we all find different sources to read and share our independent conclusions.

For those who know German Die Wahrheit und was wirklich passierte is a classic that’s worth watching on the subject of media quality. It was held in 2007 at the ChaosComputerCongress and one of the conclusions is that most newspapers are sawdust and people should read more primary sources.

Danke

Or you read: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Propaganda_model

The problem isn’t just one of propaganda whereby certain interests get pushed. It’s also one of general lack of deep insight of the reporter in the subject they are reporting on and their necessity to simplify matters.

The argument is that many people make the experience that if they encounter a newspaper article about a subject where they have domain knowledge they discover that the article is full of mistakes. If you then generalize that observation over the whole newspaper it leads to the conclusion that the paper isn’t better then sawdust.

The excercise for the reader would be to go to the average science section of a prestigious newspaper from ten years ago, look at the study based on which the article is based, on what happened in the topic afterwards and then judge how informative the article was. Then the next step is to ask yourself what it would mean if that quality level would generalize over the whole newspaper.

Or when you attended a gathering/event then read about it and think that that was an entirely different event.

“newspaper from ten years ago, … what happened in the topic afterwards and then judge how informative the article was”

As a German you will know the saying: “Nichts ist so alt wie die Zeitung von gestern.” → “Nothing is as old as yesterdays paper.”

N.N. Taleb calls it noise.

At fist it is either wrong or without consequence or propaganda, then it is outdated. A historian will find 99% of all “news” to be little more as an “interesting time piece” at best representative for the thinking and style of the era.