Even babies think that objects have individual identities. If you show an infant a ball rolling behind a screen, and then a moment later, two balls roll out, the infant looks longer at the expectation-violating event. Long before we’re old enough to talk, we have a parietal cortex that does spatial modeling: that models individual animals running or rocks flying through 3D space.

And this is just not the way the universe works. The difference is experimentally knowable, and known. Grasping this fact, being able to see it at a glance, is one of the fundamental bridges to cross in understanding quantum mechanics.

If you shouldn’t start off by talking to your students about wave/particle duality, where should a quantum explanation start? I would suggest taking, as your first goal in teaching, explaining how quantum physics implies that a simple experimental test can show that two electrons are entirely indistinguishable—not just indistinguishable according to known measurements of mass and electrical charge.

To grasp on a gut level how this is possible, it is necessary to move from thinking in billiard balls to thinking in configuration spaces; and then you have truly entered into the true and quantum realm.

In previous posts such as Joint Configurations and The Quantum Arena, we’ve seen that the physics of our universe takes place in a multi-particle configuration space.

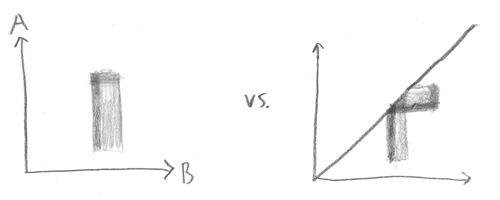

The illusion of individual particles arises from approximate factorizability of a multi-particle distribution, as shown at left for a classical configuration space.

If the probability distribution over this 2D configuration space of two classical 1D particles, looks like a rectangular plaid pattern, then it will factorize into a distribution over A times a distribution over B.

In classical physics, the particles A and B are the fundamental things, and the configuration space is just an isomorphic way of looking at them.

In quantum physics, the configuration space is the fundamental thing, and you get the appearance of an individual particle when the amplitude distribution factorizes enough to let you look at a subspace of the configuration space, and see a factor of the amplitude distribution—a factor that might look something like this:

This isn’t an amplitude distribution, mind you. It’s a factor in an amplitude distribution, which you’d have to multiply by the subspace for all the other particles in the universe, to approximate the physically real amplitude distribution.

Most mathematically possible amplitude distributions won’t factor this way. Quantum entanglement is not some extra, special, additional bond between two particles. “Quantum entanglement” is the general case. The special and unusual case is quantum independence.

Reluctant tourists in a quantum universe talk about the bizarre phenomenon of quantum entanglement. Natives of a quantum universe talk about the special case of quantum independence. Try to think like a native, because you are one.

I’ve previously described a configuration as a mathematical object whose identity is “A photon here, a photon there; an electron here, an electron there.” But this is not quite correct. Whenever you see a real-world electron, caught in a little electron trap or whatever, you are looking at a blob of amplitude, not a point mass. In fact, what you’re looking at is a blob of amplitude-factor in a subspace of a global distribution that happens to factorize.

Clearly, then, an individual point in the configuration space does not have an identity of “blob of amplitude-factor here, blob of amplitude-factor there”; so it doesn’t make sense to say that a configuration has the identity “A photon here, a photon there.”

But what is an individual point in the configuration space, then?

Well, it’s physics, and physics is math, and you’ve got to come to terms with thinking in pure mathematical objects. A single point in quantum configuration space, is the product of multiple point positions per quantum field; multiple point positions in the electron field, in the photon field, in the quark field, etc.

When you actually see an electron trapped in a little electron trap, what’s really going on, is that the cloud of amplitude distribution that includes you and your observed universe, can at least roughly factorize into a subspace that corresponds to that little electron, and a subspace that corresponds to everything else in the universe. So that the physically real amplitude distribution is roughly the product of a little blob of amplitude-factor in the subspace for that electron, and the amplitude-factor for everything else in the universe. Got it?

One commenter reports attaining enlightenment on reading in Wikipedia:

‘From the point of view of quantum field theory, particles are identical if and only if they are excitations of the same underlying quantum field. Thus, the question “why are all electrons identical?” arises from mistakenly regarding individual electrons as fundamental objects, when in fact it is only the electron field that is fundamental.’

Okay, but that doesn’t make the basic jump into a quantum configuration space that is inherently over multiple particles. It just sounds like you’re talking about individual disturbances in the aether, or something. As I understand it, an electron isn’t an excitation of a quantum electron field, like a wave in the aether; the electron is a blob of amplitude-factor in a subspace of a configuration space whose points correspond to multiple point positions in quantum fields, etc.

The difficult jump from classical to quantum is not thinking of an electron as an excitation of a field. Then you could just think of a universe made up of “Excitation A in electron field over here” + “Excitation B in electron field over there” + etc. You could factorize the universe into individual excitations of a field. Your parietal cortex would have no trouble with that one—it doesn’t care whether you call the little billiard balls “excitations of an electron field” so long as they still behave like little billiard balls.

The difficult jump is thinking of a configuration space that is the product of many positions in many fields, without individual identities for the positions. A configuration space whose points are “a position here in this field, a position there in this field, a position here in that field, and a position there in that field”. Not, “A positioned here in this field, B positioned there in this field, C positioned here in that field” etc.

You have to reduce the appearance of individual particles to a regularity in something that is different from the appearance of particles, something that is not itself a little billiard ball.

Oh, sure, thinking of photons as individual objects will seem to work out, as long as the amplitude distribution happens t factorize. But what happens when you’ve got your “individual” photon A and your “individual” photon B, and you’re in a situation where, a la Feynman paths, it’s possible for photon A to end up in position 1 and photon B to end up in position 2, or for A to end up in 2 and B to end up in 1? Then the illusion of classicality breaks down, because the amplitude flows overlap:

In that triangular region where the distribution overlaps itself, no fact exists as to which particle is which, even in principle—and in the real world, we often get a lot more overlap than that.

I mean, imagine that I take a balloon full of photons, and shake it up.

Amplitude’s gonna go all over the place. If you label all the original apparent-photons, there’s gonna be Feynman paths for photons A, B, C ending up at positions 1, 2, 3 via a zillion different paths and permutations.

The amplitude-factor that corresponds to the “balloon full of photons” subspace, which contains bulges of amplitude-subfactor at various different locations in the photon field, will undergo a continuously branching evolution that involves each of the original bulges ending up in many different places by all sorts of paths, and the final configuration will have amplitude contributed from many different permutations.

It’s not that you don’t know which photon went where. It’s that no fact of the matter exists. The illusion of individuality, the classical hallucination, has simply broken down.

And the same would hold true of a balloon full of quarks or a balloon full of electrons. Or even a balloon full of helium. Helium atoms can end up in the same places, via different permutations, and have their amplitudes add just like photons.

Don’t be tempted to look at the balloon, and think, “Well, helium atom A could have gone to 1, or it could have gone to 2; and helium atom B could have gone to 1 or 2; quantum physics says the atoms both sort of split, and each went both ways; and now the final helium atoms at 1 and 2 are a mixture of the identities of A and B.” Don’t torture your poor parietal cortex so. It wasn’t built for such usage.

Just stop thinking in terms of little billiard balls, with or without confused identities. Start thinking in terms of amplitude flows in configuration space. That’s all there ever is.

And then it will seem completely intuitive that a simple experiment can tell you whether two blobs of amplitude-factor are over the same quantum field.

Just perform any experiment where the two blobs end up in the same positions, via different permutations, and see if the amplitudes add.

No Individual Particles

Followup to: Can You Prove Two Particles Are Identical?, Feynman Paths

Even babies think that objects have individual identities. If you show an infant a ball rolling behind a screen, and then a moment later, two balls roll out, the infant looks longer at the expectation-violating event. Long before we’re old enough to talk, we have a parietal cortex that does spatial modeling: that models individual animals running or rocks flying through 3D space.

And this is just not the way the universe works. The difference is experimentally knowable, and known. Grasping this fact, being able to see it at a glance, is one of the fundamental bridges to cross in understanding quantum mechanics.

If you shouldn’t start off by talking to your students about wave/particle duality, where should a quantum explanation start? I would suggest taking, as your first goal in teaching, explaining how quantum physics implies that a simple experimental test can show that two electrons are entirely indistinguishable —not just indistinguishable according to known measurements of mass and electrical charge.

To grasp on a gut level how this is possible, it is necessary to move from thinking in billiard balls to thinking in configuration spaces; and then you have truly entered into the true and quantum realm.

In previous posts such as Joint Configurations and The Quantum Arena, we’ve seen that the physics of our universe takes place in a multi-particle configuration space.

If the probability distribution over this 2D configuration space of two classical 1D particles, looks like a rectangular plaid pattern, then it will factorize into a distribution over A times a distribution over B.

In classical physics, the particles A and B are the fundamental things, and the configuration space is just an isomorphic way of looking at them.

In quantum physics, the configuration space is the fundamental thing, and you get the appearance of an individual particle when the amplitude distribution factorizes enough to let you look at a subspace of the configuration space, and see a factor of the amplitude distribution—a factor that might look something like this:

This isn’t an amplitude distribution, mind you. It’s a factor in an amplitude distribution, which you’d have to multiply by the subspace for all the other particles in the universe, to approximate the physically real amplitude distribution.

Most mathematically possible amplitude distributions won’t factor this way. Quantum entanglement is not some extra, special, additional bond between two particles. “Quantum entanglement” is the general case. The special and unusual case is quantum independence.

Reluctant tourists in a quantum universe talk about the bizarre phenomenon of quantum entanglement. Natives of a quantum universe talk about the special case of quantum independence. Try to think like a native, because you are one.

I’ve previously described a configuration as a mathematical object whose identity is “A photon here, a photon there; an electron here, an electron there.” But this is not quite correct. Whenever you see a real-world electron, caught in a little electron trap or whatever, you are looking at a blob of amplitude, not a point mass. In fact, what you’re looking at is a blob of amplitude-factor in a subspace of a global distribution that happens to factorize.

Clearly, then, an individual point in the configuration space does not have an identity of “blob of amplitude-factor here, blob of amplitude-factor there”; so it doesn’t make sense to say that a configuration has the identity “A photon here, a photon there.”

But what is an individual point in the configuration space, then?

Well, it’s physics, and physics is math, and you’ve got to come to terms with thinking in pure mathematical objects. A single point in quantum configuration space, is the product of multiple point positions per quantum field; multiple point positions in the electron field, in the photon field, in the quark field, etc.

When you actually see an electron trapped in a little electron trap, what’s really going on, is that the cloud of amplitude distribution that includes you and your observed universe, can at least roughly factorize into a subspace that corresponds to that little electron, and a subspace that corresponds to everything else in the universe. So that the physically real amplitude distribution is roughly the product of a little blob of amplitude-factor in the subspace for that electron, and the amplitude-factor for everything else in the universe. Got it?

One commenter reports attaining enlightenment on reading in Wikipedia:

Okay, but that doesn’t make the basic jump into a quantum configuration space that is inherently over multiple particles. It just sounds like you’re talking about individual disturbances in the aether, or something. As I understand it, an electron isn’t an excitation of a quantum electron field, like a wave in the aether; the electron is a blob of amplitude-factor in a subspace of a configuration space whose points correspond to multiple point positions in quantum fields, etc.

The difficult jump from classical to quantum is not thinking of an electron as an excitation of a field. Then you could just think of a universe made up of “Excitation A in electron field over here” + “Excitation B in electron field over there” + etc. You could factorize the universe into individual excitations of a field. Your parietal cortex would have no trouble with that one—it doesn’t care whether you call the little billiard balls “excitations of an electron field” so long as they still behave like little billiard balls.

The difficult jump is thinking of a configuration space that is the product of many positions in many fields, without individual identities for the positions. A configuration space whose points are “a position here in this field, a position there in this field, a position here in that field, and a position there in that field”. Not, “A positioned here in this field, B positioned there in this field, C positioned here in that field” etc.

You have to reduce the appearance of individual particles to a regularity in something that is different from the appearance of particles, something that is not itself a little billiard ball.

Oh, sure, thinking of photons as individual objects will seem to work out, as long as the amplitude distribution happens t factorize. But what happens when you’ve got your “individual” photon A and your “individual” photon B, and you’re in a situation where, a la Feynman paths, it’s possible for photon A to end up in position 1 and photon B to end up in position 2, or for A to end up in 2 and B to end up in 1? Then the illusion of classicality breaks down, because the amplitude flows overlap:

In that triangular region where the distribution overlaps itself, no fact exists as to which particle is which, even in principle—and in the real world, we often get a lot more overlap than that.

I mean, imagine that I take a balloon full of photons, and shake it up.

Amplitude’s gonna go all over the place. If you label all the original apparent-photons, there’s gonna be Feynman paths for photons A, B, C ending up at positions 1, 2, 3 via a zillion different paths and permutations.

The amplitude-factor that corresponds to the “balloon full of photons” subspace, which contains bulges of amplitude-subfactor at various different locations in the photon field, will undergo a continuously branching evolution that involves each of the original bulges ending up in many different places by all sorts of paths, and the final configuration will have amplitude contributed from many different permutations.

It’s not that you don’t know which photon went where. It’s that no fact of the matter exists. The illusion of individuality, the classical hallucination, has simply broken down.

And the same would hold true of a balloon full of quarks or a balloon full of electrons. Or even a balloon full of helium. Helium atoms can end up in the same places, via different permutations, and have their amplitudes add just like photons.

Don’t be tempted to look at the balloon, and think, “Well, helium atom A could have gone to 1, or it could have gone to 2; and helium atom B could have gone to 1 or 2; quantum physics says the atoms both sort of split, and each went both ways; and now the final helium atoms at 1 and 2 are a mixture of the identities of A and B.” Don’t torture your poor parietal cortex so. It wasn’t built for such usage.

Just stop thinking in terms of little billiard balls, with or without confused identities. Start thinking in terms of amplitude flows in configuration space. That’s all there ever is.

And then it will seem completely intuitive that a simple experiment can tell you whether two blobs of amplitude-factor are over the same quantum field.

Just perform any experiment where the two blobs end up in the same positions, via different permutations, and see if the amplitudes add.

Part of The Quantum Physics Sequence

Next post: “Identity Isn’t In Specific Atoms”

Previous post: “Feynman Paths”