The Power to Understand “God”

This is Part VI of the Specificity Sequence

“God” is a classic case of something that people should be more specific about. Today’s average college-educated person talking about God sounds like this:

Liron: Do you believe in God?

Stephanie: Yeah, I’d say I believe in God, in some sense.

Liron: Ok, in what sense?

Stephanie: Well, no one really knows, right? Like, what’s the meaning of life? Why is there something instead of nothing? Even scientists admit that we don’t understand these things. I respect that there’s a deeper kind of truth out there.

Liron: Ok, I remember you said your parents are Christian and they used to make you go to church sometimes… are you still a Christian now or what?

Stephanie: At this point I wouldn’t be dogmatic about any one religion, but I wouldn’t call myself an atheist either. Maybe I could be considered agnostic? I feel like all the different religions have an awareness that there’s this deep force, or energy, or whatever you want to call it.

Liron: Ok, so, um… do you pray to God?

Stephanie: No, I don’t really say prayers anymore, but I prayed when I was younger and I appreciate the ritual. The Western religions believe in praying to God and being saved. The Eastern religions believe in meditation and striving toward enlightenment. There are a lot of different paths to the same spiritual truth… I just have faith that there is a truth, you know?

What did you think of Stephanie’s answers? I’m pretty sure most people would be like, “Yeah, sounds right to me. I’m just glad you didn’t ask me to explain it. I really would have struggled if you’d put me on the spot like that, but she did a pretty good job.”

If we were asking Stephanie about her fantasy sports team picks, we’d expect her to explain what she believes and why she believes it, grounding her claims in specific predictions about the outcomes of future sportsball games.

But there’s a social norm that when we ask someone about “God”, it’s okay for them to squirt an ink cloud of “truth”, “energy”, “enlightenment”, “faith”, and so on, and make their getaway.

Let’s activate our specificity powers. We’ve seen that the best way to define a term is often to ground the term, to slide it down the ladder of abstraction. How would Stephanie ground her concept of “God”? Her attempts might look like this:

The universal force that people pray to.

The energy that makes the universe exist.

The destination that all religions lead to.

Ooh, do you notice how these descriptions of “God” have an aura of poetic mystery if you read them out loud? Unfortunately, any mystery they have means they’re doing a shitty job grounding the concept in concrete terms. I’m calling in dialogue-Liron.

Liron: Let’s ground the concept of “God”. You said you currently believe in God. What if tomorrow you didn’t believe in God anymore? What would be noticeably different about a world where you didn’t believe in God?

Stephanie: Well, on most days I don’t think about God much, so it might not affect my day. But God still exists whether you believe in Her or not, don’t you think?

Liron: Ok, let’s say for the sake of argument that I believe there’s no God. Then it sounds like we don’t see eye to eye about the universe, right?

Stephanie: Right.

Liron: And let’s say we’ve never talked with each other about God before, so neither of us knows yet whether the other believes in God or not. If we just go about our lives, when would we first notice that we don’t see eye to eye about the universe?

Stephanie: Maybe in a discussion like this, where someone starts talking about who believes in God, and I say “yes” and you say “no”.

Liron: Yeah, that’s what I suspected: The way to ground your concept of “God” is nothing more than “A word that some people prefer to say they believe in.” Which is just about as empty as it gets for words.

Stephanie: You’re jumping to that conclusion pretty fast. If I believe in God and you don’t, I think there’s more to it than just a choice I make to say that I believe in God.

Liron: Ok, so to help me ground your concept of “God”, tell me another specific scenario where I can observe some consequence of the fact that you believe in God, besides hearing the words “I believe in God” coming out of your mouth.

Stephanie: How about: I think that the universe has some kind of higher purpose.

Liron: Ok, so not only does believing in “God” imply that you’re likely to speak the words “I believe in God”, it also implies that you’re likely to speak the words “the universe has some kind of higher purpose”. I still suspect that in order to ground the concept of “God”, I don’t need to pay attention to anything in the world beyond the verbalizations you make when you’re having what you think are deep conversations.

It would also be interesting to ask Stephanie what Sam Harris asked a guest on his Making Sense podcast: “Would you believe in God if God didn’t exist?” Is there something in our external reality, beyond your own preferences for what words you were taught to say and what words you feel good saying, that can in principle be flipped one way or the other to determine whether or not you believe in God? I suspect the answer is no.

Now consider how the dialogue would have gone differently if I were talking to Bob, a bible literalist who believes that God answers his prayers:

Liron: Let’s say we’ve never talked with each other about God before, so neither of us knows yet whether the other believes in God or not. If we just go about our lives, when would we first notice that we don’t see eye to eye about the universe?

Bob: You’ll see me kneeling in prayer, and then you’ll see my prayers are more likely to get answered. Like when I know someone is in the hospital, I pray for their speedy recovery, and the folks I pray for will usually recover more speedily than the folks no one prays for.

Liron: Oh okay, cool. So we can ground your “God” as “the thing which makes people recover in the hospital faster when you pray for them”. Congratulations, that’s a nicely grounded concept whose associated phenomena extend beyond verbalizations you make.

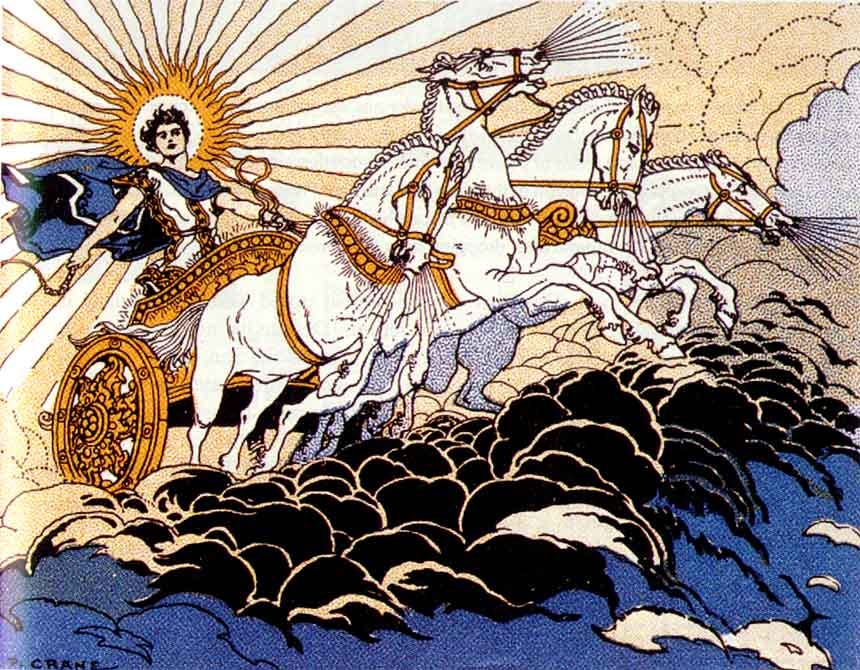

Unlike Stephanie’s concept, Bob’s concept of “God” has earned the respectable status of being concrete. Bob’s prayer-answering God is as concrete as Helios, the chariot-pulling sun god.

I wonder if this party died when someone invented dark glasses to look at the sun with.

From a specificity standpoint, Stephanie’s concept of God is empty and weird, while Bob’s concept is completely normal and fine.

On the other hand, Bob’s concept is demonstrably wrong, and Stephanie’s isn’t. But it’s easy to be not-wrong when you’re talking about empty concepts. Here’s Stephanie being not-wrong about “spirits”:

Liron: Do you believe in spirits?

Stephanie: Yes

Liron: Ok, how do I ground “spirit”? How do I know when to label something as a spirit?

Stephanie: They’re a special type of beings.

Liron: Do you hear them speak to you?

Stephanie: No, I don’t think so.

Liron: If tomorrow spirits suddenly didn’t exist anymore, do you think you’d notice?

Stephanie: Hm, I don’t know about that.

Ladies and gentleman, she’s not wrong!

Of course, she’s not right either, but that’s okay with her. She doesn’t enjoy talking about “God”, and when she does she’s only playing to not-lose, not playing to win.

Equipped with the power of specificity, it’s easy for us to observe the emptiness of Stephanie’s “God”. It’s harder for us to explain why all the intelligent Stephanies of the world are choosing to utter the sentence, “I believe in [empty concept]”.

Eliezer Yudkowsky traces the historical lineage of how Bobs (God-believers) begat Stephanies (God-believers-in):

Back in the old days, people actually believed their religions instead of just believing in them. The biblical archaeologists who went in search of Noah’s Ark did not think they were wasting their time; they anticipated they might become famous. Only after failing to find confirming evidence — and finding disconfirming evidence in its place — did religionists execute what William Bartley called the retreat to commitment, “I believe because I believe.”

In Taboo Your Words, Eliezer uses the power of specificity to demolish the nice-sounding claim that religions are all paths to the same universal truth:

The illusion of unity across religions can be dispelled by making the term “God” taboo, and asking them to say what it is they believe in; or making the word “faith” taboo, and asking them why they believe it.

Though mostly they won’t be able to answer at all, because it is mostly profession in the first place, and you cannot cognitively zoom in on an audio recording.

In your own life, try to avoid the word “God”, and just discuss what you specifically want to discuss. If your conversation partner introduces the word “God”, your best move is to ground their terms. Establish what specifically they’re talking about, then have a conversation about that specific thing.

Next post: The Power to Be Emotionally Mature

A believer in God is an easy target. Can you find a deep belief in something that you are holding and go through the same steps you outlined above for Stephanie?

It turns out to be hard to be clear and specific about the basic concepts of materialism, like time, space, matter and energy.

All I asked Stephanie to do is ground her term “God”. Terms like “space” are easily groundable in hundreds of ways.

For example for “space”: I can use my eyes to estimate the distance between people standing in a field. If the people then seem to be trying their hardest to run toward each other, I expect to observe a minimum amount of time before I’ll see their distances hit near-zero, proportional to the distance apart they are.

If tomorrow there were no space, one way I could distinguish that alternate reality from current reality is by observing the above grounding getting falsified.

Naively defining space as the gaps between stuff produces as much clarity and conviction as defining god as a warm fuzzy feeling. Which could conceivably go missing.

Yes “a warm fuzzy feeling triggered by me thinking of the word ‘God’” could be a valid grounding of “God”; in fact Stephanie’s character probably might ground it that way, since she’s intentionally written as a character who merely possesses belief in belief in God.

So whats superior about your epistemology?

Stephanie suffers from belief-in-belief (which she wrongly thinks is just an ordinary belief with an external referent) and I don’t

Are you sure? You seem to believe in materialism, without being able to give proper explanations of space, time, matter and energy.

I did give a valid grounding of “space”.

That would depend on the meaning of “grounding”.

I define “grounding” in How Specificity Works

Then you have two problems. One of the is that the warm fuzzy feeling definition of God is a perfectly good grounding. The other is that large tracts of science and maths can’t be grounded in sensation. How do you ground imaginary numbers or infinity or the interior of an event horizon?

I’d refer you to https://wiki.lesswrong.com/wiki/Highly_Advanced_Epistemology_101_for_Beginners

I’ve read it.

Yes, easy once armed with the tools of rationality.

LessWrong has the effect of gradually making people lose belief in God, and move beyond the whole frame of arguing about God to all kinds of interesting new framings and new arguments (e.g. simulation universes, decision theories, and AI alignment).

The goal of this post is to briefly encapsulate the typically longer experience of having LW dissolve “God” by asking what “God” specifically refers to in the mind of the believer.

I like to think that my deep beliefs all have specific referents to not be demolishable, so it’s hard for me to know where to start looking for one that doesn’t. Feel free to propose ideas. But if I don’t personally struggle with the weakness that I’m helping others overcome, that seems ok too.

I meant that a believer in God and supernatural in general is an easy target for a non-believer armed with the standard arguments of atheism.

Yes and no. That’s how I moved from being an atheist to being an agnostic, given the options above. There are just too many “rational” possibilities instrumentally indistinguishable from God.

I call it the folly of a bright dilettante. You are human with all the human failings, which includes deeply held mind projection fallacies. A deeply held belief feels like an unquestionable truth from the inside, so much so, we are unlikely to even notice that it’s just a belief, and defend it against anyone who questions it. If you want an example, I’ve pointed out multiple times that privileging the model of objective reality (the map/territory distinction) over other models is one of those ubiquitous beliefs. Now that you have read this sentence, pause for a moment and notice your emotions about it. Really, take a few seconds. List them. Now compare it with the emotions a devout person would feel when told that God is just a belief. If you are honest with yourself, then you are likely to admit that there is little difference. Actually, a much likelier outcome is skipping the noticing entirely and either ignoring the uncomfortable question as stupid/naive/unenlightened, or rushing to come up with arguments defending your belief. So, if you have never demolished your own deeply held belief, and went through the emotional anguish of reframing your views unflinchingly, you are not qualified to advise others how to do it.

Ya I was hoping for an example, thanks :)

My first emotion was “Come on, you want to challenge objective reality? That’s a quality belief that’s table stakes for almost all productive discussions we can have!”

Then I thought, “Okay fine, no problem, I’m mature and introspective enough to do this rationality exercise, I don’t want to be a hypocrite to change others’ minds about religion without allowing my own mind to be changed by the same sound methods, plus anyway this community will probably love me if I do by chance have a big fundamental mind change on this topic, so I don’t care much if I do or not, although it’ll become a more time-consuming exercise to have such an epiphany.”

Then I thought, “Okay but I don’t even know where to begin imagining what a lack of objective reality looks like, it just feels like confusion, similar to when I try to imagine e.g. a non-reductionist universe with ontologically fundamental mental entities.”

For my first emotion, sure, there’s little difference in the reaction between me and a God-believer. But for my subsequent introspection, I think I’m doing better and being more rational than most God-believers. That’s why I consider myself a pretty skilled rationalist! Perhaps I have something to show for spending thousands of hours reading LW posts?

I think I have the power to have crises of faith. FWIW, I realized I personally do “believe in God” in the sense that I believe Bostrom’s Simulation Hypothesis has more than a 50% chance of being true, and it’s a serviceable grounding of the term “God” to refer to an intelligence running the simulation—although it may just be alien teenagers or something, so I certainly don’t like bringing in the connotations of the word “God”, but it’s something right?

I would think it is like dreaming.. an individual having experiences that aren’t shared with or comparable to anyone else’s.

Well. Now you have stumbled upon another standard fallacy, argument from the failure of imagination. If you look up various non-realist epistemologies, it could be a good start.

Uh. Depends on how you define being rational. If you follow Eliezer and define it as winning, then there are many believers that are way ahead of you.

If you aren’t controlling for confounding factors, like being born into an extremely rich family, and instead just compare the most successful believers and the most successful rationalists (or, in this case, Liron in particular), of course we’re going to get blown out of the water. There are how many rationalists, again? The interesting thing is to ask, if we control for all relevant factors, does rationality training have a good effect size? This is a good question, with quite a bit of previous discussion.

If you’ll allow me to guess one potential response, let’s suppose there’s no effect. What then—are we all being “irrational”, and is the entire rationality project a failure? Not necessarily. This depends on what progress is being made (as benefits can be nonlinear in skill level). For example, maybe I’m learning Shaolin Kenpo, and I go from white to yellow belt. I go up to a buff guy on the street and get my ass kicked. Have I failed to learn any Shaolin Kenpo?

Of course, I wasn’t trying to argue the claim, I was just reporting my experience.

Great! Well done! Noticing your own emotions is a great step most aspiring rationalists lack.

Thanks

Isn’t the map/territory distinction implied by minds not being fundamental to the universe, which follows from the heavily experimentally demonstrated hypothesis that the universe runs on math?

I don’t want to get into this discussion now, I’ve said enough about my views on the topic in other threads. Certainly “the heavily experimentally demonstrated hypothesis that the universe runs on math” is a vague enough statement to not even be worth challenging, too much wiggle room.

If you ask her how the universes higher purpose shapes her expectations, she might say that she expects God to think this universe to yet have an interesting story to tell, because otherwise God wouldn’t bother to keep it instantiated. Therefore, she might see it as less likely that some nerds in a basement accidentally turn the world into paperclips, because that would be a stupid story.

In that case, I would act like a scientist making observations of her mental model of reality, and file away “the cause of a lower probability that nerds in a basement will turn the world into paperclips” as part of a grounding of “God”. I would keep making observations and pull them together into a meaningful hypothesis, which would probably have the same epistemic status as Bob’s god Helios

Placebo effects area a real thing. If one truly takes Bob’s grounding then it is not obvious that it is factually incorrect. If “dark matter” means “whatever causes this expansion” then “whatever causes this healing” probably hits a whole bunch of aspects of reality.

It’s problematic when a person is judged for having illdefined stances when their characterization comes from the interluctor. For example asking about going to church as if it had some relevance to believing in god steps outside of a narrowly tailored question or presupposes that these are connected.

If I have a fixed understanding that aether theoyr is better than it’s precedessors and have a very fixed idea what a wave is I am likely to not listen what the stance of the other is. Aaron could be very well versed in relativity and conceptual work on what is a wave and what is simultaneuity might be essential to the discussion.

The Liron-Stephanie could also be read as Liron using vague concepts where Stephanie closely and narrowly desccribes what it means to her. If somebody asks a question like “What is bear divided by nine?” you might be asking “Do you think that bear is some kind of number or that nine is some kind of animal and is this division some sort of arithmetical or agricultural operation?” the discussion might go vague because we don’t know what we are talking about. A question like “Do you believe in God?” is polymorphic in the sense that it has multiple sensible ways it can be posed. For example it could mean “Do you participate in utilising forces you do not understand for personal benefit?”, “Are you an active participant in a congeration?”, “Do you find the universe meaningful and are not in a state of nihilism?”

The patience of discussion-liron runs out pretty fast and is likely because of preconceptions that “higher purpose” is likely to be empty. Wondering if it is not empty what it could look like I was imagining a scenario where a person with “higher purpose” is more likely to forgo the use of lethal force in a struggle for survival or critical resources (giving “benefit of the doubt” that the local situation can be lost but life/existence overall still won). That kind of scenario is really unwiedly to tell as an example and requires connecting many systems to have the cause and effect relationship. It would be way more natural to connect concepts on adjacent abstraction layers. And connecting god with “higher purpose” is one step down on that abstraction ladder. A more healthy discussion would encourage that and recursively step down until requested concreteness level was reached.

Think about the discussion of “what would be different in my daily life if many worlds interpretation was correct over copenhagen interpretation that isn’t just socialising about physics memes”. It would be a really challenging discussion and probably not that enlightening about physics. One could also say that because the quantum physics stays the same regardless of interpretation the distinction is in danger of being empty. But if the “content” is found over which direction is better for physics research then “research direction truths” would be even more indirect. So while I think it is important that the different systems and layers are relevant to each other doing all of them in a single bound is seldomly a good move. And deducing that if you can’t do such connections in a single jump then your concepts must be empty is throwing plenty of baby out with the water.

But if we’re being honest with each other, we both know that Bob’s grounding is factually incorrect, right? It’s not trivial to lay out the justification for this knowledge that we both possess, it requires training in epistemology and Occam’s razor. But a helpful intuition pump is Marshall Brain’s question: Why won’t God heal amputees? This kind of thought experiment shows the placebo effect to be a better hypothesis than Bob’s God.

In your example of an unfairly-written dialogue, when Slider says at the end “Seems contradictory and crazy”, it feels like the most unfair part is when you don’t let Aaron respond one more time. I think the single next line of dialogue would be very revealing:

If you think that I have written a dialogue where you can add just one line of dialogue to make a big difference to the reader’s takeaway, feel free to demonstrate it, because I consider this to be a sign of an unfairly-written dialogue.

You claim that my questions to Stephanie were overly vague, but if that were the case, then Stephanie could simply say “The way your questions are constructed seems vague and confusing to me. I’m confused what you’re specifically trying to ask me.” But that wouldn’t fit in the dialogue because my questions weren’t the source of vagueness; Stephanie’s confusion was the source of vagueness.

I purposely designed a dialogue where Stephanie really is pure belief-in-belief. I think this accurately represents most people in these kinds of discussions. I could write a longer dialogue where I give Stephanie more opportunity to have subtle coherent beliefs reveal themselves, but given who her character is, they won’t.

In your analogy with a dialogue about Stephanie-the-many-worlds-believer, I would expect Stephanie to sharply steer the discussion in the direction of Occam’s razor and epistemology, if she knew what she was talking about. Similarly, she could have sharply steered somewhere if she had a coherent meaning about believing in God beyond trivial belief-in-belief.

How can groundings be correct or incorrect? If it walks like a duck, eats like a duck, swims like a duck and I call it God it’s a duck by different name. It might be that Bobs god is placebo. To the extent opened in the example dialogue it is synonymous. Any additonal facets are assumed and when the point of the exchance was to disambiguate what we mean great weight must be placed on what was actually said. If someone is not believing but only beliefs in belief as an external person it would be an inaccurate belief to think they belief.

It would seem in the text that the given definition of god would lay out enough information that the existence of impact on healing factors could be checked for and the text claims such a check would show no impact. Now if you believe that pacebo is a thing you would probably think that a setup where some patients are visited by their doctors vs one where they ar not visited by their doctor would show impact. If the test for healing was to have the prayer by their medside it would seem mostly analogous to the doctor visit and should have comparable impact. Such a test would show impact. In arguing why the impact result is wrong one needs to argue how the test setup did not test for the correct hypothesis. What bob gave us wasn’t exactly rocket science “I pray—they heal” (I think I assumed that a “pray campaign” would involve visiting but it was not infact mentioned). If the procedure involved artificial hiding or no contact prayer that could be significantly different how it would happen “in the wild”. An a prayer might geniunely be a practise that differ which would perform differently. Depression medication is warranted enough for having impact comparable to placebo, then deploying a prayer campaign to a patient that would not get placebo benefits otherwise would be medically warranted.

I have trouble evaluating what giving such a definition would look like. Most definitions i can find care to get the mathematics represented. And while it doesn’t have an explicit medium reference it’s unclear whether the mathematical device connected with physical theory avoids forming a medium at all. That you avoid physics at the mathematics level is not surprising at all. And just like a duck can’t avoid being a duck for beign called God that the theory doesn’t have an explicit part called “medium” doesn’t mean it doesn’t sport one. I would probably benefit from actually receiving such a definition and going over the question for reals. But in any case it refers back to more entrenched beliefs were things rely on other things and simple point changes to the theories are unlikely.

It might not be the most insightful thing but it could be a thing that is associable even if the theory is hazy and might be typical of how such belief systems funciton within a psychology. It would still be very vague and would warrant closer inspection.

I get that you are trying to target folks that are very neglient in their belief details. But I think it risk falsely processing a lot of different kinds of folks as that type. If you start talking to a person and they have some grasp of their concepts or they do have meaning in their words it would be prudent to catch on that even if the beliefs were strange, wrong or vaguely expressed. It might also be that the sanity waterline is geniunely different in different environments. In my experience faith-healers are looked down upon by religious people and they try to mitigate it. That is it’s not the faith that is seen as the problem but that they are unironically trying to use magic.

That discussion strategy for many-worlds would try to dodge having to be specific. The start-up idea did not receive an out for trying to sharply direct the discussion but was counted as being not specific.

Thanks for trying my “write one more line of the dialogue” challenge. I think that our two attempts are quite different and sufficiently illustrate my point.

The difference is not obvious to me. How they are relevantly different? You just seem to favour lore from one magisterium.

You’re having Stephanie admit to dialogue-Liron’s claim that she possesses mere belief-in-belief, i.e. her term “God” isn’t grounded in anything outside of her own mind.

Well that is a good contrast on what kind of difference is seeked.

I thought not being grounded was about having only theory that has no implications for anything.

If I claim “I am sad” that is not empty just becuase it refers to my mind. I could be wrong about that and sadness is grounded.

In a similar way “that axe is sharp” could be construed to mean about intentions to use the axe. In an extreme interpretation it doesn’t specify any physical properties about the axe because the same axe could appear dull to another person. It could mean something “I am about to use that axe to chop down some wood” which would be solely about psychological stances towards the future. So this would be an argument line to say that “that axe is sharp” is not grounded. While the absurdity is strong with “sharp” consider “hotness” as in sexyness. Trying to ground it out into particular biological or physical features isn’t a trivial thing at all.

If an axe can groundedly be good for cutting then an environment can be suitable for living and saying that the universe is suitable for prospering expresses a similar kind of “fit for use” property.

To put it another way, “grounding” is pretty ambiguous between defining a term and justifying the existence of an entity.

I don’t think that’s an accurate characterization of grounding

You usually justify the existence of a concept althought it can often take the form that some particular species appears in the ontology. There are real cases when you want to justify entities for example whether a particular state should exist or not. Then you are not just arguing whether it should be understood in the terms of a state or some other organizational principle but what actually happens in the world.

I would like to see shminux challenge addressed here. Let’s pick another faith based case—or even the atheist position (which I would argue is just as much about faith as the religious persons). I agree with the position that rationality leads not to no belief (in god or some other position) but an agnostic position.

Sure, see that thread.

Ok, I think you’re asking me to ground my atheism-belief, like why am I not agnostic?

Since I don’t think that you think I should be agnostic about e.g. Helios, I would ask you to first clarify your question by putting forth a specific hypothesis that you think I should be agnostic rather than atheist about.

I do not see that it is my position to suggest or argue that you be anything. I would suggest the “burden of proof” why X does y will always belong with X.

If atheism is the faith position you want to defend or challenge with your power of specifics that is fine with me. It would be engaging shminux’s suggestion rather than sidestepping it.

I am not defending or refuting anything here but will point out that atheism is a statement about something not existing. Proving something does not exist is a highly problematic exercise.

No, for any hypothesis H, it’s on average equally “problematic” to believe its probability is 1% as it is to believe its probability is 99%.

This doesn’t quite engage with the parent.

This is obviously true because there’s an isomorphism between hypotheses and their negations, and “for any hypothesis” includes both. (There might also be other, less obvious reasons why it’s true.)

But the set of hypotheses “X does not exist” doesn’t contain both sides of the isomorphism, so the obvious argument doesn’t carry through.

And I don’t think the conclusion is true, either, though I wouldn’t want to say much more without being specific about what set of entities we’re considering. (All logically possible ones? Physically possible? Entities that people claim to have communicated with? Of course it’s not your job to do this, the parent was underspecified.)

I figured anyone who thinks proving non-existence is extra hard also probably lacks a sufficiently thought-out concept of “existence” to convincingly make that claim :)

But ok, to engage more with the parent: My atheism takes the form “For all God-concepts I’ve heard of, my attempt to make them specific has either yielded something wrong like Helios, or meaningless like belief-in-belief or perhaps a bad word choice like ‘God is probability’”.

If the set of all God-concepts I’ve heard were empty, I wouldn’t have the need to say I’m an atheist. That’s why the burden of proof is actually on the God-concept-proposers.

This feels like a framing problem. For me to think that my room isn’t full of apples, I don’t need to prove it isn’t full of apples, I just need to assign significantly higher probability to apples not bursting out of my windows.

What would you do if she replied,”My concept of God is a pantheistic one based on the all-pervading and so far unexplained zero-point energy, without which the Universe would not exist. It may or may not be intelligent, but so far it does appear to meet the criteria of immortal, invisible, and omnipresent”?

I’d ask: If one day your God stopped existing, would anything have any kind of observable change?

Seems like a meaningless concept, a node in the causal model of reality that doesn’t have any power to constrain expectation, but the person likes it because their knowledge of the existence of the node in their own belief network brings them emotional reward.