DSLT 1. The RLCT Measures the Effective Dimension of Neural Networks

TLDR; This is the first post of Distilling Singular Learning Theory (DSLT), an introduction to which can be read at DSLT0. In this post I explain how singular models (like neural networks) differ from regular ones (like linear regression), give examples of singular loss landscapes, and then explain why the Real Log Canonical Threshold (aka the learning coefficient) is the correct measure of effective dimension in singular models.

When a model class is singular (like neural networks), the complexity of a parameter in parameter space needs a new interpretation. Instead of being defined by the total parameters available to the model , the complexity (or effective dimensionality) of is defined by a positive rational called the Real Log Canonical Threshold (RLCT), also known as the learning coefficient. The geometry of the loss is fundamentally defined by the singularity structure of its minima, which measures. Moreover, in regular models like linear regression the RLCT is , but in singular models it satisfies in general. At its core, then, Sumio Watanabe’s Singular Learning Theory (SLT) shows the following key insight:

The RLCT is the correct measure of effective dimensionality of a model .

Watanabe shows that the RLCT has strong effects on the learning process: it is the correct generalisation of model complexity in the Bayesian Information Criterion for singular models, and therefore plays a central role in the asymptotic generalisation error, thereby inheriting the name “learning coefficient”.

In this first post, after outlining the Bayesian setup of SLT, we will start by defining what a singular model is and explain what makes them fundamentally different to regular models. After examining different examples of singular loss landscapes, we will define the RLCT to be the scaling exponent of the volume integral of nearly true parameters, and conclude by summarising how this quantity correctly generalises dimensionality.

Preliminaries of SLT

The following section introduces some necessary technical terminology, so use it as a reference point, not necessarily something to cram into your head on a first read through. A more thorough setup can be found in [Car21, Chapter 2], which follows [Wat09] and [Wat18].

SLT is established in the Bayesian paradigm, where the Bayesian posterior on the parameter space is the primary object of focus, containing information on which parameters correspond to “good” models.

Our statistical learning setup consists of the following data:

A dataset , where for each is an input and is an output (so we are in the supervised learning setting).

We suppose the sequence in is independent and identically distributed according to a true distribution . For our purposes, we assume the true distribution of inputs to be known, but the true distribution of outputs to be unknown.

We then choose a model class defined by parameters in a compact parameter space that contains the origin. We hope to find model parameters that will adequately approximate the truth, or in other words, learn how to accurately predict an output given an input. For example, a model class could be a fixed neural network architecture with Gaussian noise, as below.

We can select a prior distribution of our choosing[1] that is non-zero on , so .

Using this data, the error of the model on the dataset is defined by the empirical negative log likelihood (NLL), ,

where is the model likelihood. [2] [3]

This gives rise to the Bayesian posterior of defined by [4]

where the partition function (or in Bayesian terms the evidence) is given by

The partition function measures posterior density, and thus contains a lot of macroscopic data about a system. Inspired by its role in physics, and for theoretical ease, we consider the free energy

Performing asymptotic analysis on (and therefore ) is the main task of SLT. The learning goal is to find small regions of parameter space with high posterior density, and therefore low free energy.

Though we never have access to the truth in the learning procedure, for theoretical purposes we nonetheless define the empirical entropy of the true distribution

Even though this quantity is always inaccessible in real settings, there is almost sure convergence as to a constant that doesn’t depend on , [5]

To study the posterior, we define the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the truth and the model,

which is the infinite-data limit of its empirical counterpart,

The KL divergence is usually thought of as a “loss metric”[6] between the truth and and the model since

for all , and;

if and only if for all and all .

As such, I will colloquially refer to as the loss landscape. [7] The current state of results in SLT require to be an analytic function, but it seems likely that the results can be generalised to non-analytic settings with suitable hypotheses and constraints.

To analyse where the loss is minimised, we are then lead to defining the set of true parameters,

We say that the true distribution is realisable by the model class if is non empty, that is, there exists some such that for all . Despite being unrealistic in real world applications, this is nonetheless an important starting point to the theory, which will then generalise to the set of optimal parameters in DSLT2.

We are going to restrict our attention to a particular kind of model: neural networks with Gaussian noise. We will formally define a neural network in a following chapter of this sequence, but for now it suffices to say that it is a function with inputs and outputs defined by some parameter . Then our model density is going to be given by

From here on in, we will assume we are working with a (model, truth, prior) triple as specified in this section.

Loss in our setting

To put these technical quantities into perspective, let me make clear two key points:

Under the regression model, the NLL is equivalent to the mean-squared error of the neural network on the dataset (up to a constant),

In the realisable case where , the KL divergence is just the euclidean distance between the model and the truth adjusted for the prior measure on inputs,

Singular vs Regular Models

What is a singular model?

The key quantity that distinguishes regular and singular models is the Fisher information matrix , whose entries are defined by

It can be shown that when evaluated at a point on the set of true parameters , the Fisher information matrix is simply the Hessian of , so

A regular statistical model class is one which is identifiable (so implies that ), and has positive definite Fisher information matrix for all . Regular model classes, such as standard linear regression, are the backbone of classical statistics for which all pre-exisiting literature on Bayesian statistics applies. But, from the point of view of SLT, regular model classes are… boring.

If a model class is not regular, then it is strictly singular. The non-identifiability condition can be easily dealt with, but it is the degeneracy of the Fisher information matrix that fundamentally changes the nature of the posterior and its asymptotics. We will say a model defined by a fixed (not necessarily a true parameter) is strictly singular if the Fisher information at the point, , is degenerate, meaning

- , where is the number of dimensions in parameter space , or equivalently;

.

Then the model class is strictly singular if there exists a such that is degenerate. A singular model class can be either regular or strictly singular—Watanabe’s theory thus generalises regular models, regardless of the model non-identifiability or degenerate Fisher information.

It can be easily shown that, under the regression model, is degenerate if and only the set of derivatives

is linearly dependent.

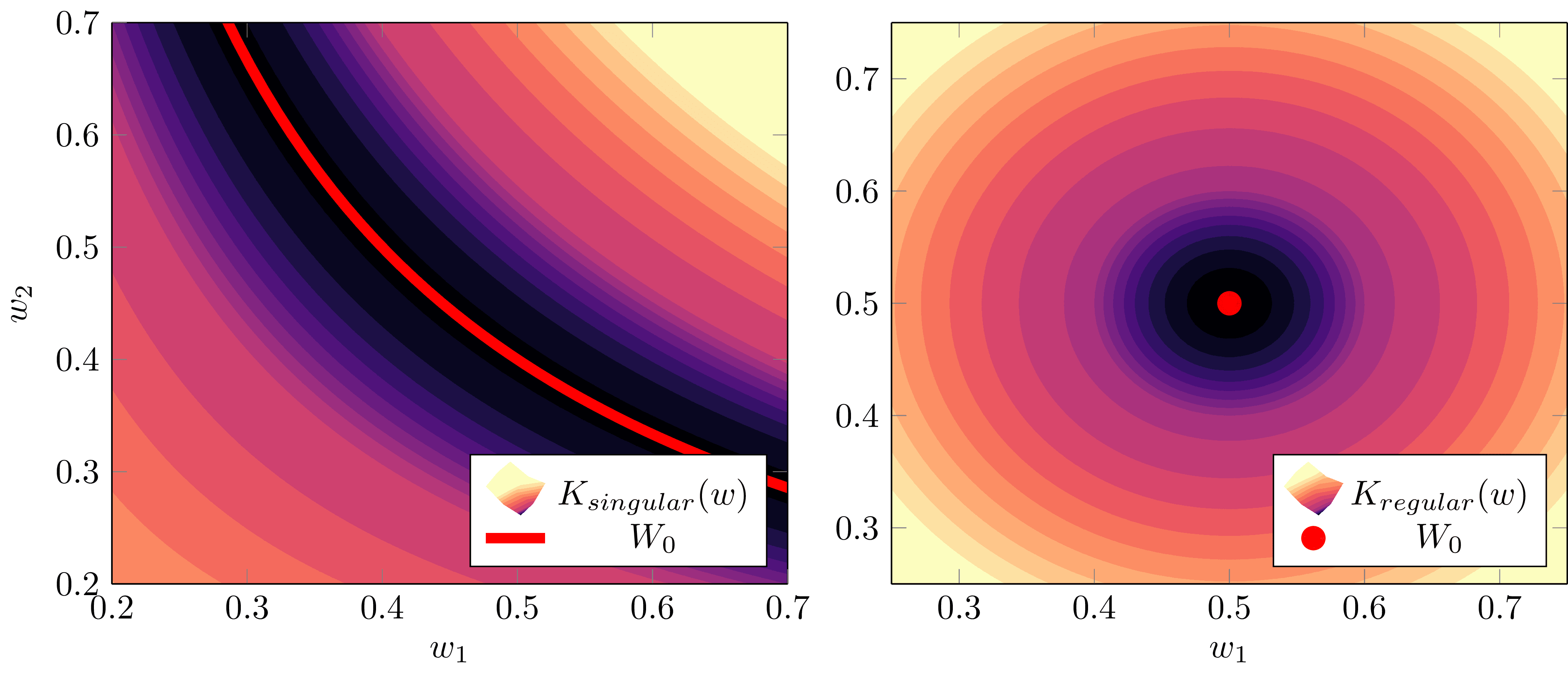

In regular models, the set of true parameters consists of one point. But in singular models, the degeneracy of the Fisher information matrix means is not restricted to being one point, or even a set of isolated points—in general, these local minima of are connected together in high-dimensional structures [8]. In strictly singular models, the true parameters are degenerate singularities [9] of , and thus cannot be approximated by a quadratic form near these points. This is the fundamental reason the classical theory of Bayesian statistics breaks down.

Watanabe states that “in singular statistical models, the knowledge or grammar to be discovered corresponds to singularities in general” [Wat09]. With this in mind, it is unsurprising that the following widely used models are all examples of singular models:

Layered neural networks

Gaussian, binomial, multinomial and other mixture models

Reduced rank regression

Boltzmann machines

Bayes networks

Hidden Markov models

Singular models are characterised by features like: having hierarchical structure, being made of superposition of parametric functions, containing hidden variables, etc., all in the service of obtaining hidden knowledge from random samples.

Classical Bayesian inference breaks down for singular models

There are two key properties of regular models that are critical to Bayesian inference as :

Asymptotic normality: The posterior of regular models converges in distribution to a -dimensional normal distribution centred at the maximum likelihood estimator [Vaa07]:

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC): The free energy of regular models asymptotically looks like the BIC as , where and is the dimension of parameter space :

At the core of both of these results is an asymptotic expansion that strongly depends on the Fisher information matrix being non-degenerate at true parameters . It’s instructive to see why this is, so let’s derive the BIC to see where shows up.

Deriving the Bayesian Information Criterion only works for regular models

For the sake of this calculation, let us assume . Taking our cues from [Kon08], suppose (thus is a maximum likelihood estimator and satisfies ). We can Taylor expand the NLL as

where is the Hessian. Since we are analysing the asymptotic limit , we can relate this Hessian to the Fisher information matrix,

By definition is a minimum of , so , so we can expand the partition function as

Here’s the crux: if is non-degenerate (so the model is regular), then we can perform this integral in good-faith knowing that it will always exist. In that case, the second term involving vanishes since it is the first central moment of a normal distribution, so we have

since the integrand is the integral of a -dimensional multivariate Gaussian . Notice here that this is the same distribution that arises in the asymptotic normality result, a theorem that has the same core, but requires more rigorous probability theory to prove. If is degenerate, then it is non-invertible, meaning the above formulas cannot hold.

The free energy of this ensemble is thus

and so ignoring terms less than in , we arrive at the Bayesian Information Criterion

This quantity can be understood as an accuracy-complexity tradeoff, where the complexity of the model class is defined by . We will elaborate on this more in DSLT2 but for now, you should just believe that the Fisher information is a big deal. Generalising this procedure (and therefore the BIC) for singular models, is the heart of SLT.

Examples of Singular Loss Landscapes

In essence, the Fisher information matrix describes something about the effective dimensionality or complexity of a model . When a model class is regular, the effective dimensionality of every point is simply , the number of parameters available to the model. But in the singular case, a new notion of effective dimensionality is required to adequately describe the complexity of a model. We’re now going to look at two cases of singular models [10] - or more precisely, loss landscapes that correspond to singular models—to motivate this generalisation. We’ll start with the easier case where one or more parameters are genuinely “free”.

Sometimes singularities are just free parameters

Example 1.1: Suppose we have parameters afforded to a model such that , which has a Hessian given by

Taking the critical point , we have and so , thus the model is singular. In this case, since for all , we could simply throw out the free parameter and define a regular model with parameters that has identical geometry , and therefore defines the same input-output function, .

This example is called a minimally singular case. Suppose with integers such that , and after some change of basis[11] we may write a local expansion of as the sum of squares,

where are positive coefficients. Then the Fisher information matrix has the form

where is the square zero matrix. Perhaps then we could define the “effective dimensionality” of as being , which is the number of tangent directions in parameter space in which the model changes—the number of “non-free” parameters—and just discard the “free” parameters that are normal to

Sure! We can do that, and if we did, our BIC derivation would carry out fine and we would just replace by in the final formula. So the minimally singular case is easy to handle.

But this doesn’t always work.

But not all singularities are free parameters

Defining the effective dimensionality at as seems nice in theory, but turns out to give nonsensical answers pretty quickly—it is not a full enough description of the actual geometry at play.

Example 1.2: Suppose instead that . Then the Hessian is

At the critical point the Fisher information is

which is obviously degenerate.

If we used our notion of effective dimensionality from before, we would say the model defined by had effective dimension of . But this would be ridiculous—clearly there are more than zero “effective dimensions” in this model, a term that would intuitively imply was identically zero, which it clearly is not. Thus, we need a different way of thinking about effective dimensionality.

The Real Log Canonical Threshold (aka the Learning Coefficient)

In this section we are going to explain the key claim of this post: that effective dimensionality in singular models is measured by a positive rational number called the Real Log Canonical Threshold, also known as the learning coefficient.

Dimensionality as a volume co-dimension

Taking inspiration from Weyl’s famous Volume of Tubes paper, we can reframe dimensionality in terms of a scaling exponent of the volume of “nearly” true parameters. To explain this, we will generalise the minimally singular case above. The following discussion follows [Wei, 22].

Assume we have a partition as before with such that , where is the number of non-free parameters and is the number of free parameters. For any we can consider the set of almost true parameters centred at (which, without loss of generality, we will take to be ),

and an associated volume function

As long as the prior is non-zero on it does not affect the relevant features of the volume, so we may assume that it is a constant in the first directions and is a normal distribution in the remaining . Then since , we can write

The right integrand is some constant that doesn’t depend on , and for the left we can make the substitution , hence

Recognising the integrand as the volume of the -ball, a constant that does not depend on , we see that

Then the dimension arises as the scaling exponent of , which can be extracted via the following ratio of volumes formula for some :

This scaling exponent, it turns out, is the correct way to think about dimensionality of singularities.

Watanabe shows in Theorem 7.1 of [Wat09] that in general, for any singular model defined by , the volume integral centred at has the form

where is a positive rational number called the Real Log Canonical Threshold (RLCT) associated to the “most singular point” in . This is the quantity that generalises the dimensionality of a singularity. What’s more, different singularities in can have different RLCT values, and thereby different “effective dimensionalities”. As suggested above, the RLCT can then be defined by this volume formula:

An example of fractional dimension

Example 1.3: To build intuition for what a “fractional dimension” is, consider a model with parameters with KL divergence given by , which is singular since . A simple calculation shows that for this KL divergence,

meaning and so the “effective dimensionality” is .

Meanwhile, in the case, , so the effective dimensionality is 1.

The RLCT can be read off when is in normal crossing form

I may have presented the previous section suggesting that the RLCT is trivial to calculate. In general, this couldn’t be further from the truth. But in one special case, it is. For this discussion we will ignore the prior, i.e. we will set it to be uniform on .

One dimensional case

As we just saw in Example 1.3, in the one dimensional case where for some , the RLCT is simply . In fact, if we can express in the form

for non-negative integers and unique , then the RLCT associated to each singularity is simply . But, Watanabe shows that it is the smallest local RLCT (and thus the highest exponent in ) that dominates the free energy, thus defining the global RLCT where

Example 1.4 This example is going to be very relevant in DSLT2. If we have

with true parameters and , then the local RLCT associated to each singularity is

The global RLCT is thus

Multidimensional case

Suppose now that so . Suppose without loss of generality that is a true parameter for . If we can write the KL divergence in normal crossing form near ,

then the RLCT is given by

The multiplicity of each coordinate is the number of elements in that equal

This generalises this above case in the following sense:

Example 1.5 Suppose now that we have a two dimensional KL divergence of the form

Then, in a neighbourhood of the singularity , the KL divergence is approximately

Thus, the RLCT associated to is

with multiplicity

On the other hand, near the singularity the KL divergence is, up to a prefactor, approximately

so the RLCT associated to is

with multiplicity . So, in this case the global RLCT is , which we will see in DSLT2 means that the posterior is most concentrated around the singularity .

Resolution of Singularities

In Algebraic Geometry and Statistical Learning Theory, Watanabe shows that algebraic geometry plays a central role in governing the behaviour of statistical models, and a highly non-trivial one in singular models especially. This rich connection between these two deep mathematical fields is, in my eyes, both profound and extremely beautiful.

The remarkable insight of Watanabe is that in fact any KL divergence, under appropriate hypotheses (such as analyticity), can be written in normal crossing form near a singularity of . To do so, he invokes one of the fundamental theorems of algebraic geometry: Hironaka’s Resolution of Singularities. The content of this theorem and its implications go well beyond the scope of this sequence. But, I will briefly mention its role in the theory as it relates to the RLCT. For a more detailed introduction to this part of the story, see [Wat09, Section 1.4].

The theorem guarantees the existence of a -dimensional analytic manifold and a real analytic map

such that for each coordinate of one can write

where each and are non-negative integers, is the Jacobian determinant of and is a real analytic function. The global RLCT is then defined by

and the global multiplicity is the maximum multiplicity over .

From this point on in the sequence, when you see the word “desingularise”, what you should think is “put into normal crossing form near a singularity”.

The RLCT measures the effective dimensionality of a model

Succinctly, the RLCT of a singularity generalises the idea of dimension because:

If a model defined by is regular, then

If a model defined by is minimally singular where is the number of non-free parameters, then

In general, for any singular model the RLCT satisfies (by Theorem 7.2 of [Wat09])

In particular, if there are non-free parameters then

In order to find the asymptotic form of the free energy as , Watanabe desingularises near each singularity using the Resolution of Singularities. The RLCT then directly substitutes into the place of in the BIC formula, which gives rise to the Widely Applicable Bayesian Information Criterion (WBIC)

In DSLT2, we will explain the implications of the WBIC and what it tells us about the profound differences between regular and singular models.

Appendix 1 - The other definition of the RLCT

In this post we have defined the RLCT as the scaling exponent of the volume integral of nearly true parameters. This result, whilst the most intuitive, is presented in the reverse order to how Watanabe originally defines the RLCT in [Wat09]. Alternatively, we can consider the zeta function

and show that it has a Laurent series given by

where is a holomorphic function, are coefficients, each is ordered such that , and is the largest order of the pole .

Then the Real Log Canonical Threshold of our (model, truth, prior) triple is with multiplicity .

This is a key piece of machinery in using distribution theory to expand the partition function . In the end, the smallest and its multiplicity are the dominant terms in the expansion, and a further calculation in [Wat09, Theorem 7.1] shows how .

To see why is necessary, and why this definition of the RLCT matters to the free energy formula proof, see the sketch of the proof in [Wat09, pg31-34].

References

[Car21] - Liam Carroll, Phase Transitions in Neural Networks (thesis)

[Wat09] - Sumio Watanabe, Algebraic Geometry and Statistical Learning Theory (book)

[Wat18] - Sumio Watanabe, Mathematical Theory of Bayesian Statistics (book)

[KK08] - Konishi, Kitagawa, Information Criteria and Statistical Modelling (book)

[Vaa07] - van der Vaart, Asymptotic Statistics (book)

[Wei22] - Susan Wei, Daniel Murfet et al., Deep Learning is Singular, and That’s Good (paper)

- ^

In the finite case, the choice of prior is a philosophical matter, as well as a mathematical tractability matter. But as , most results in Bayesian statistics show to be irrelevant so long as it satisfies some reasonable conditions. This is also true in SLT. ↩︎

- ^

This should remind you of the Gibbs ensemble from statistical physics—not coincidentally, either. ↩︎

- ^

For theoretical, philosophical, and computational purposes, we also define the tempered posterior to be

where is the inverse temperature. This plays an important role in deriving the free energy formula and can be thought of as controlling the “skinniness” of the posterior. In our regression model below, it is actually the inverse variance of the Gaussian noise. ↩︎

- ^

By Bayes’ rule we have . The form written here follows from some simplification of terms and redefinitions, see page 10 of the thesis.

- ^

We can define an expectation over the dataset for some function as

In particular, we define the entropy of the true conditional distribution to be

and the (non-empirical) negative log loss to be

It is easy to show that and , and so by the law of large numbers there is almost sure convergence and . Analogous definitions show

- ^

Though it isn’t a true metric due to its asymmetry in and , and since it doesn’t satisfy the triangle inequality. ↩︎

- ^

Note here that since , we can reasonably call both and the loss landscape since they differ only by a constant (as ).

- ^

Or more precisely, a real analytic set.

- ^

Since , and , and is degenerate. ↩︎

- ^

Based on , it is relatively easy to reconstruct a model that genuinely yields a given function, so we may happily pretend we have said model when we pull such a loss function from thin air. ↩︎

- ^

Which is guaranteed to exist since the Hessian is a real symmetric matrix (and thus so is ), so it can be diagonalised. ↩︎

- From SLT to AIT: NN generalisation out-of-distribution by (4 Sep 2025 15:20 UTC; 114 points)

- The Local Interaction Basis: Identifying Computationally-Relevant and Sparsely Interacting Features in Neural Networks by (20 May 2024 17:53 UTC; 108 points)

- You’re Measuring Model Complexity Wrong by (11 Oct 2023 11:46 UTC; 93 points)

- DSLT 0. Distilling Singular Learning Theory by (16 Jun 2023 9:50 UTC; 92 points)

- Degeneracies are sticky for SGD by (16 Jun 2024 21:19 UTC; 56 points)

- 's comment on Lucius Bushnaq’s Shortform by (20 Sep 2024 12:44 UTC; 47 points)

- Three ways interpretability could be impactful by (18 Sep 2023 1:02 UTC; 47 points)

- Deep Learning is cheap Solomonoff induction? by (7 Dec 2024 11:00 UTC; 46 points)

- Estimating effective dimensionality of MNIST models by (2 Nov 2023 14:13 UTC; 41 points)

- DSLT 2. Why Neural Networks obey Occam’s Razor by (18 Jun 2023 0:23 UTC; 31 points)

- Basics of Bayesian learning by (14 Jan 2025 10:00 UTC; 12 points)

- 's comment on Leon Lang’s Shortform by (5 Jul 2023 9:15 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Gradient descent might see the direction of the optimum from far away by (29 Jul 2023 7:57 UTC; 5 points)

- 's comment on DSLT 2. Why Neural Networks obey Occam’s Razor by (25 Jun 2023 22:46 UTC; 2 points)

Thank you for this wonderful article! I read it fairly carefully and have a number of questions and comments.

Should I think of this as being equal to p((Yi)|(Xi)), and would you call this quantity p(Dn)? I was a bit confused since it seems like we’re not interested in the data likelihood, but only the conditional data likelihood under model p.

And to be clear: This does not factorize over i because every data point informs w and thereby the next data point, correct?

But the free energy does not depend on the parameter, so how should I interpret this claim? Are you already one step ahead and thinking about the singular case where the loss landscape decomposes into different “phases” with their own free energy?

I think the first expression should either be an expectation over XY, or have the conditional entropy H(Y|x) within the parantheses.

I briefly tried showing this and somehow failed. I didn’t quite manage to get rid of the integral over y. Is this simple? (You don’t need to show me how it’s done, but maybe mentioning the key idea could be useful)

The rest of the article seems to mainly focus on the case of the Fisher information matrix. In particular, you didn’t show an example of a non-regular model where the Fisher information matrix is positive definite everywhere.

Is it correct to assume models which are merely non-regular because the map from parameters to distributions is non-injective aren’t that interesting, and so you maybe don’t even want to call them singular? I found this slightly ambiguous, also because under your definitions further down, it seems like “singular” (degenerate Fisher information matrix) is a stronger condition then “strictly singular” (degenerate Fisher information matrix OR non-injective map from parameters to distributions).

What is x in this formula? Is it fixed? Or do we average the derivatives over the input distribution?

Hhm, I thought having a singular model just means that some singularities are degenerate.

One unrelated conceptual question: when I see people draw singularities in the loss landscape, for example in Jesse’s post, they often “look singular”: i.e., the set of minimal points in the loss landscape crosses itself. However, this doesn’t seem to actually be the case: a perfectly smooth curve of loss-minimizing points will consist of singularities because in the direction of the curve, the derivative does not change. Is this correct?

I think you forgot a |w=w0 in the term of degree 1.

Could you explain why that is? I may have missed some assumption on φ(w) or not paid attention to something.

Hhm. Is the claim that if the loss of the function does not change along some curve in the parameter space, then the function itself remains invariant? Why is that?

Are you sure this is the correct formula? When I tried computing this by hand it resulted in 2/log(a), but maybe I made a mistake.

General unrelated question: is the following a good intuition for the correspondence of the volume with the effective number of parameters around a singularity? The larger the number of effective parameters λ around w0, the more K(w) blows up around w0 in all directions because we get variation in all directions, and so the smaller the region where K(w) is below ϵ. So λ contributes to this volume. This is in fact what it does in the formulas, by being an exponent for small ϵ.

Do you currently expect that gradient descent will do something similar, where the parameters will move toward singularities with low RLCT? What’s the state of the theory regarding this? (If this is answered in later posts, feel free to just refer to them)

Also, I wonder whether this could be studied experimentally even if the theory is not yet ready: one could probably measure the RLCT around minimal loss points by measuring volumes, and then just check whether gradient descent actually ends up in low-RLCT regions. Maybe this is what you do in later posts. If this is the case, I wonder whether I should be surprised or not: it seems like the lower the RLCT, the larger the number of (fractional) directions where the loss is minimal, and so the larger the basin. So for purely statistical reasons, one may end up in such a region instead of isolated loss-minimizing points of high RLCT.

I think these are helpful clarifying questions and comments from Leon. I saw Liam’s response. I can add to some of Liam’s answers about some of the definitions of singular models and singularities.

1. Conditions of regularity: Identifiability vs. regular Fisher information matrix

As Liam said, I think the answer is yes—the emphasis of singular learning theory is on the degenerate Fisher information matrix (FIM) case. Strictly speaking, all three classes of models (regular, non-identifiable, degenerate FIM) are “singular”, as “singular” is defined by Watanabe. But the emphasis is definitely on the ‘more’ singular models (with degenerate FIM) which is the most complex case and also includes neural networks.

As for non-identifiability being uninteresting, as I understand, non-regularity arising from certain kinds of non-local non-identifiability can be easily dealt with by re-parametrising the model or just restricting consideration to some neighbourhood of (one copy of) the true parameter, or by similar tricks. So, the statistics of learning in these models is not strictly-speaking regular to begin with, but we can still get away with regular statistics by applying such tricks.

Liam mentions the permutation symmetries in neural networks as an example. To clarify, this symmetry usually creates a discrete set of equivalent parameters that are separated from each other in parameter space. But the posterior will also be reflected along these symmetries so you could just get away with considering a single ‘slice’ of the parameter space where every function is represented by at most one parameter (if this were the only source of non-identifiability—it turns out that’s not true for neural networks).

It’s worth noting that these tricks don’t generally apply to models with local non-identifiability. Local non-identifiability =roughly there are extra true parameters in every neighbourhood of some true parameter. However, local non-identifiability implies that the FIM is degenerate at that true parameter, so again we are back in the degenerate FIM case.

2. Linear independence condition on Fisher information matrix degeneracy

Yeah I remember also struggling to parse this statement when I first saw it. Liam answered but in case it’s still not clear and/or someone doesn’t want to follow up in Liam’s thesis, x is a free variable, and the condition is talking about linear dependence of functions of x.

Consider a toy example (not a real model) to help spell out the mathematical structure involved: Let f(x,w)=(w1+2w2)x so that ∂∂w1f(x,w)=x and ∂∂w2f(x,w)=2x. Then let g and h be functions such that g(x)=x and h(x)=2x.. Then the set of functions {g,h} is a linearly dependent set of functions because h−2g=0.

3. Singularities vs. visually obvious singularities (self-intersecting curves)

Right, as Liam said, often[1] in SLT we are talking about singularities of the Kullback-Leiber loss function. Singularities of a function are defined as points where the function is zero and has zero gradient. Since K is non-negative, all of its zeros are also local (actually global) minima, so they also have zero gradient. Among these singularities, some are ‘more singular’ than others. Liam pointed to the distinction between degenerate singularities and non-degenerate singularities. More generally, we can use the RLCT as a measure of ‘how singular’ a singularity is (lower RLCT = more singular).

As for the intuition about visually reasoning about singularities based on the picture of a zero set: I agree this is useful, but one should also keep in mind that it is not sufficient. These curves just shows the zero set, but the singularities (and their RLCTs) are defined not just based on the shape of the zero set but also based on the local shape of the function around the zero set.

Here’s an example that might clarify. Consider two functions J,K:R2→R such that J(x,y)=xy and K(x,y)=x2y2. Then these functions both have the same zero set {(x,y):x=0 ∨ y=0}. That set has an intersection at the origin. Observe the following:

Both J(0,0)=0 and ∇J(0,0)=→0, so the intersection is a singularity in the case of J.

The other points on the zero set of J are not singular. E.g. if y=0 but x≠0, then ∇J(x,0)=(0,x)≠→0.

Even though K has the exact same zero set, all of its zeros are singular points! Observe ∇K(x,y)=(2xy2,2x2y), which is zero everywhere on the zero set.

In general, it’s a true intuition that intersections of lines in zero sets correspond to singular points. But this example shows that whether non-intersecting points of the zero set are singular points depends on more than just the shape of the zero set itself.

In singular learning theory, the functions we consider are non-negative (Kullback—Leibler divergence), so you don’t get functions like J with non-critical zeros. However, the same argument here about existence of singularities could be extended to the danger of reasoning about the extent of singularity of singular points based on just looking at the shape of the zero set: the RLCT will depend on how the function behaves in the neighbourhood, not just on the zero set.

One exception, you could say, is in the definition of strictly singular models. There, as we discussed, we had a condition involving the degeneracy of the Fisher information matrix (FIM) at a parameter. Degenerate matrix = non-invertible matrix = also called singular matrix. I think you could call these parameters ‘singularities’ (of the model).

One subtle point in this notion of singular parameter is that the definition of the FIM at a parameter w involves setting the true parameter to w. For a fixed true parameter, the set of singularities (zeros of KL loss wrt. that true parameter) will not generally coincide with the set of singularities (parameters where the FIM is degenerate).

Alternatively, you could consider the FIM condition in the definition of a non-regular model to be saying “if a model would have degenerate singularities at some parameter if that were the true parameter, then the model is non-regular”.

Thanks for the answer mfar!

Thanks! Apparently the proof of the thing I was wondering about can be found in Lemma 3.4 in Liam’s thesis. Also thanks for your other comments!

Thanks for the comment Leon! Indeed, in writing a post like this, there are always tradeoffs in which pieces of technicality to dive into and which to leave sufficiently vague so as to not distract from the main points. But these are all absolutely fair questions so I will do my best to answer them (and make some clarifying edits to the post, too). In general I would refer you to my thesis where the setup is more rigorously explained.

The partition function is equal to the model evidence Zn=p(Dn), yep. It isn’t equal to p((Yi)|(Xi)),(I assume i is fixed here?) but is instead expressed in terms of the model likelihood and prior (and can simply be thought of as the “normalising constant” of the posterior),

p(Dn)=∫Wφ(w)n∏i=1p(yi,xi|w)dwand then under this supervised learning setup where we know q(xi), we have p(yi,xi|w)=p(yi|xi,w)q(xi). Also note that this does “factor over i” (if I’m interpreting you correctly) since the data is independent and identically distributed.

Yep, you caught me—I was one step ahead. The free energy over the whole space W is still a very useful quantity as it tells you “how good” the best model in the model class is. But Fn by itself doesn’t tell you much about what else is going on in the loss landscape. For that, you need to localise to smaller regions and analyse their phase structure, as presented in DSLT2.

Ah, yes, you are right—this is a notational hangover from my thesis where I defined EX to be equal to expectation with respect to the true distribution q(y,x). (Things get a little bit sloppy when you have this known q(x) floating around everywhere—you eventually just make a few calls on how to write the cleanest notation, but I agree that in the context of this post it’s a little confusing so I apologise).

See Lemma A.2 in my thesis. One uses a fairly standard argument involving the first central moment of a Gaussian.

Yep, the rest of the article does focus on the case where the Fisher information matrix is degenerate because it is far more interesting and gives rise to an interesting singularity structure (i.e. most of the time it will yield an RLCT λ<d2). Unless my topology is horrendously mistaken, if one has a singular model class for which every parameter has a positive definite Fisher information, then this implies the non-identifiability condition simply means you have a set of isolated points w1,…,wn that all have the same RLCT d2. Thus the free energy will only depend on their inaccuracy Ln(w), meaning every optimal parameter has the same free energy—not particularly interesting! An example of this would be something like the permutation symmetry of ReLU neural networks that I discuss in DSLT3.

I have clarified the terminology in the section where they are defined—thanks for picking me up on that. In particular, a singular model class can be either strictly singular or regular—Watanabe’s results hold regardless of identifiability or the degeneracy of the Fisher information. (Sometimes I might accidentally use the word “singular” to emphasise a model which “has non-regular points”—the context should make it relatively clear).

Refer to Theorem 3.1 and Lemma 3.2 in my thesis. The Fisher information involves an integral wrt q(x)dx, so the Fisher information is degenerate iff that set is dependent as a function of x, in other words, for all x values in the domain specified by q(x) (well, more precisely, for all non-measure-zero regions as specified by q(x)).

Typo—thanks for that.

Correct! When we use the word “singularity”, we are specifically referring to singularities of K(w) in the sense of algebraic geometry, so they are zeroes (or zeroes of a level set), and critical points with ∇K(w(0))=0. So, even in regular models, the single optimal parameter is a singularity of K(w) - it just a really, really uninteresting one. In SLT, every singularity needs to be put into normal crossing form via the resolution of singularities, regardless of whether it is a singularity in the sense that you describe (drawing self-intersecting curves, looking at cusps, etc.). But for cartoon purposes, those sorts of curves are good visualisation tools.

Typo—thanks.

If you expand that term out you find that

∫W(w−w0)T∂φ∂w∣∣w=w0exp(−(w−w0)TI(w0)(w−w0))dw=∂φ∂w∣∣w=w0∫W(w−w0)Texp(−(w−w0)TI(w0)(w−w0))dw=0because the second integral is the first central moment of a Gaussian. The derivative of the prior is irrelevant.

This is a fair question. When concerning the zeroes, by the formula for K(w) when the truth is realisable one shows that

W0={w|f(x,w)=f(x,w0)},so any path in the set of true parameters (i.e. in this case the set W0={(w1,w2)|w0=0andw2∈R}) will indeed produce the same input-output function. In general (away from the zeroes of K(w)), I don’t think this is necessarily true but I’d have to think a bit harder about it. In this pathological case it is, but I wouldn’t get bogged down in it—I’m just saying “K(w) tells us one parameter can literally be thrown out without changing anything about the model”. (Note here that w2 is literally a free parameter across all of W).

Ah! Another typo—thank you very much. It should be

λ=2limε→0log(V(aε)/V(ε))loga.I think that’s a very reasonable intuition to have, yep! Moreover, if one wants to compare the “flatness” between 110w2 versus w4, the point is that within a small neighbourhood of the singularity, a higher exponent (RLCTs of 12 and 14 respectively here) is “much flatter” than a low coefficient (the 110). This is what the RLCT is picking up.

We do expect that SGD is roughly equivalent to sampling from the Bayesian posterior and therefore that it moves towards regions of low RLCT, yes! But this is nonetheless just a postulate for the moment. If one treats K(w) as a Hamiltonian energy function, then you can apply a full-throated physics lens to this entire setup (see DSLT4) and see that the critical points of K(w) strongly affect the trajectories of the particles. Then the connection between SGD and SLT is really just the extent to which SGD is “acting like a particle subject to a Hamiltonian potential”. (A variant called SGLD seems to be just that, so maybe the question is under what conditions / to what extent does SGD = SGLD?). Running experiments that test whether variants of SGD end up in low RLCT regions of K(w) is definitely a fruitful path forward.

Thanks for the answer Liam! I especially liked the further context on the connection between Bayesian posteriors and SGD. Below a few more comments on some of your answers:

I think I still disagree. I think everything in these formulas needs to be conditioned on the X-part of the dataset. In particular, I think the notation p(Dn) is slightly misleading, but maybe I’m missing something here.

I’ll walk you through my reasoning: When I write (Xi) or (Yi), I mean the whole vectors, e.g., (Xi)i=1,…,n. Then I think the posterior compuation works as follows:

p(w∣Dn)=p(w∣(Yi),(Xi))=p((Yi)∣(Xi),w)⋅p(w∣(Xi))p((Yi)∣(Xi)).That is just Bayes rule, conditioned on (Xi) in every term. Then, p(w∣(Xi))=φ(w) because from Xalone you don’t get any new information about the conditional q(Y∣X) (A more formal way to see this is to write down the Bayesian network of the model and to see that w and Xi are d-separated). Also, conditioned on w, p is independent over data points, and so we obtain

p(w∣Dn)=1p((Yi)∣(Xi))⋅e−nLn(w)⋅φ(w).So, comparing with your equations, we must have Zn=p((Yi)∣(Xi)). Do you think this is correct?

Btw., I still don’t think this “factors over i”. I think that

Zn≠∏ni=1p(Yi∣Xi).

The reason is that old data points should inform the parameter w, which should have an influence on future updates. I think the independence assumption only holds for the true distribution and the model conditioned on w.

Right. that makes sense, thank you! (I think you missed a factor of n/2, but that doesn’t change the conclusion)

Thanks also for the corrected volume formula, it makes sense now :)

Shouldn’t the second singularity be at the point w=0?

I’m a bit confused here. First, I take it that α labels coordinate patches? Second, consider the very simple case with d=2 and K(w)=w21+w22. What g would put K into the stated form?

Hi, thank you for the sequence. Do you know if there is any way to get access the Watanabe’s book for free ?

If the cost is a problem for you, send a postal address to daniel.murfet@gmail.com and I’ll mail you my physical copy.

Only in the illegal ways, unfortunately. Perhaps your university has access?