[NOTE: This post has been edited extensively to account for key info I had missed.]

As we move to ban TikTok, and as we use that move as an excuse to pass a new supercharged Patriot Act for the entire internet, every other social network including Twitter moves to transform itself into TikTok.

Twitter under Elon Musk is unique in that it has a second goal, a mission of the utmost importance. To charge you $8.

This means that Twitter increasingly pushes its users towards its For You feed.

My previous understanding was that this feed was also going fully algorithmic to match TikTok’s, and would also only include posts from verified (meaning ‘paying’) accounts. Even your own followers, I believed, were to be excluded.

Elon then said he ‘forgot to mention’ that this would not be the case, and anyone you do follow will still be included. Perhaps this was indeed him forgetting to mention it, perhaps it was a reversal.

Either way, this post was temporarily unpublished until it could be reworked to account for this new information. Life comes at you fast these days.

Including followed accounts reverses much of the transformation that would have been made to the For You feed. If you like an account, you can follow that account.

The polls change remains an issue. Unverified (meaning ‘non-paying’) accounts will not be able to vote in polls. There is no indication that any amount of following, in any direction, would reverse this.

That’s on top of the new super-long Tweet options from Twitter Blue.

Elon Musk says the verification requirements are due to the threat of bots.

Neither I nor GPT-4 are optimistic about the impact of the changes. GPT-4, I think correctly, predicts loss of users, perception of elitism and misalignment of content, while the financial implications are uncertain.

When I thought your followed accounts would be excluded from For You, I thought this actually opened up a very interesting new opportunity – you could use a hybrid approach, where you used the For You tab for non-followed content, exploration and discovery, and the Following tab for a core of followed content. In theory you can still do that, if you want to move most or all your follows onto lists, but it’s tricker and higher overhead so I expect almost no one to do it, myself included.

What do all the changes to Twitter mean in practice? What should we expect? How should we adjust? Is Twitter, like mortal men, doomed to die?

This post covers the following changes and questions.

Botpocalypse Soon? Is that what is going on here? No.

View Counts and Bookmarks are now visible. That gives you better info.

A Cautionary Note on Threading. View counts are entirely front loaded here.

Twitter Blue and Long Posts.

Twitter as the new TikTok. The move to For You as a purely algorithmic feed.

Some Social Media Algorithms. What are some other algorithms to compare to?

How to Live With Twitter’s Algorithm as a Reader? Engage with caution.

What Will This Do To New User Acquisition? Good question.

How to Live With Twitter’s Algorithm as a Creator? Pay up and shift focus.

Did Twitter Murder Polls? It certainly looks a lot like they plan to do this.

What Happens to Twitter Now? A larger scale view.

Botpocalypse Soon?

Here is the announcement of the recent changes. Elon is claiming that requiring verification is necessary to shield us from the coming wave of bot content.

Yeah. No. That’s Obvious Nonsense.

The whole point of an algorithmic feed is that bot content quickly gets filtered out because it’s bot content and no one likes it. Have you ever seen a bot make it into the For You section? I don’t look at it much, but it automatically appears a bit sometimes, and I can be pretty confident that this rarely if ever happens.

How bad is the bot problem right now?

If this persisted, it would not be remotely worth the levels of disruption we are about to invoke, so the argument has to be that (1) this will quickly get much worse and (2) there are no other reasonable mitigations. I don’t buy it.

As an experiment, I looked at my current For You tab for a pre-registered 100 posts, to divide them into categories, each thread counts as one item based on the parent:

Posts by people I follow or list.

Worthwhile posts by people I don’t follow or list.

Neural (non-worthwhile) posts by clearly real people.

Negative (make my life worse) posts by clearly real people.

Suspected bot and spam posts.

Confident-that-this-is-a-bot-or-spam posts.

I ended up stopping after 50 because the answer was so overwhelmingly obvious.

32 posts by people I follow.

6 posts that were worthwhile, including 4 that I opened for viewing later.

12 neutral posts. Could say 2 are small negative because video, perhaps.

0 negative posts, 0 suspected or clear bot or spam posts.

Of the 12 neutral posts, the majority involved a reply by a follower.

My conclusion is that the current For You tab is doing a reasonable job for me of giving a selection of Tweets, were I fine with randomly not seeing some things and not knowing I hadn’t seen them.

Alas, this is exactly what makes it useless. If I have to wade through a feed that is 70% things I have already seen, that is a huge cost to using that feed. That 70% is only useful if it is reliable enough to not seek that info elsewhere, which is very much not the case. So you’re stuck, and the For You tab will remain worthless.

All right, the tab is fine now, but what about in the future?

Even if things got substantially worse, there are plenty of other ways to mitigate this that are less oppressive, if Elon Musk wanted that. We have lots of other ways to check if an account is producing quality content, and to check if a given post is plausibly worthwhile, and so on.

No, I don’t mean using iris scans.

The first and most obvious is the one Twitter is actually going to do – if you explicitly ask for something by following it, you get that account. I’d also include anyone on one of your lists. Then there are a number of other clear and hard-to-exploit mechanisms one can use to establish trust, which Twitter already uses as an explanation for showing you content. ‘Some people you follow often like their Tweets,’ for example, is a thing I sometimes see, and which seems good, as does having those you follow in turn follow someone else in sufficient quantities.

For any sufficiently large account you should have plenty of other data as well. De facto such factors seem like they should be able to allow most posts worth sharing to get through the filters. Many options. Unless, of course, you really want that $8.

I see two plausible explanations for why they’re not doing that.

The most obvious is the default. Elon Musk wants you to pay, so he’s improving the value proposition to get more people to pay. If 80% of impressions are algorithmic and you only get those by paying, and 5% of people pay, many users will get an order of magnitude or more extra impressions by paying. That’s great value.

Same with the polls. You want your voice to be heard? Pay up.

My poll verifies that yes, these changes will drive Blue subscriptions.

Notice that this was over a 15% response rate, whereas a future version of this poll would have a 1.5% response rate (and would make no sense to ask). I would rarely never run Twitter polls if I lost 90%+ of my sample size.

If the only effect here was the 6.3% quit rate versus 4.6% conversation rate, with no other effects, I presume Musk would be very happy with that result. Instead, I expect a bunch of knock-on problems.

The second plausible explanation for what Musk is up to is that cutting off non-verified posts is actually about the needs of the algorithm. Algorithms of this type need to run quickly and efficiently, and they need to gather data on all possible offerings. Limiting the pool of potential offerings, and doing so on a standardized basis, greatly eases the difficulty of making the whole plan work from an engineering perspective. That could be a major motivating factor.

The rest of the post will be analyzing the impact of the various changes.

View Counts and Bookmarks

Two new features are that you can see a Tweet’s view counts and bookmarks.

View counts are valuable. They tell you what is going on. What are people actually seeing?

You get training data on which Tweets get lots of views, which go semi-viral or full viral, which fall flat or that were effectively buried. By looking at relative counts on different posts of yours, you can see what the algorithm likes and what it doesn’t. You can also see the decay in time of how often people see something, or graph views to know what times are good to post, if you grab the data while it is available.

One need not only study this with one’s own Tweets. I am sure there are people out there training LLMs on this information.

Another use case is noticing something is buried, and helping it stay that way.

Another thing to notice is that if you respond to a reply, that reply will get substantially more views. So you are doubly incentivized not to engage in places where you don’t want more engagement. That seems good.

View counts also tell you the ratios of response. How many replies or likes or bookmarks did you get? That number is a numerator. Without the denominator, it greatly lacks context.

All of this is a huge deal on the new Twitter, because new Twitter is centrally about the algorithm and virality.

Unless you are mainly trying to talk to your friends? Extract or die.

A Cautionary Note on Threading

Another big thing view counts taught me is a proper understanding of threading.

Threads almost always drop off dramatically in views past the first Tweet and especially past the second one.

That means that not only will only the first message matter much for virality, it also means most people will only see the first Tweet. Whatever your core message is, it needs to be there in full.

The situation is not as bad as it looks, because the views for later posts are much higher engagement per view in every sense.

It still reverses the impression one would naturally have, that threading logically linked posts is a useful service and that it will encourage more views and engagement.

My new model says that it simply won’t do that. So whereas previously I would be tempted to do things like ‘I have a mega-thread of all of my link-posts to my Substack, and I add to that as I go’ I instead intentionally don’t do that. I only thread when there is no other way.

A similar note applies to replies, as they too are a form of threading. Replies have dramatically lower view counts than the original post. Thus, I now feel very comfortable replying when I want to talk directly to the original poster, while I feel discouraged from doing so in the hopes that I would reach anyone else, unless the original is already doing massive numbers.

Twitter Blue and Longer Posts

Twitter and long posts are not a good fit. I strongly believe that you do not want to go over the Tweet size limit often.

When you do something that wants to be longer than 280 characters, whenever possible, you should instead embrace the format you are in. That means either cut it down to 280, or split it into Tweets that work as part of a thread. Even if you essentially need to split into 2-3 parts, I’d still rather thread.

The only time you want to be going to Twitter Blue extra length, in my view, is when you have a unitary thing to say and it is very long. My barrier here is something like 1,000 characters. Even then, I’d use extreme caution, it’s a sign you are in the wrong format.

Twitter as the New TikTok

The For You tab will be fully algorithmic, and after April 15, unless someone explicitly and directly follows you it will include only verified accounts.

That means virality is a huge deal in the new Twitter.

Will the old Twitter still exist in parallel, for those who dare use it and the following tab? Yes, 20% of people still use that tab. And people can still choose to follow you directly, which will if anything matter more with so much non-followed content potentially excluded.

When I look at variance of hits or impressions for different posts by the same account across social media websites, it is surprising how little variance we find. Consider these statistics, I would have expected a much more skewed ratio.

A 2022 paper quantified this for TikTok and YouTube: On TikTok, the top 20% of an account’s videos get 76% of the views, and an account’s most viewed video is on average 64 times more popular than its median video. On YouTube, the top 20% of an account’s videos get 73% of the views, and an account’s most viewed video is on average 40 times more popular than its median video.

That’s not even quite the old 20%-80% rule.

Even so, consider how much a little extra oomph behind a post matters, provided you’ve paid for ‘verification.’ Virality is largely a Boolean, then you get exponential additional success if you improve. Either something can escape your immediate network, or it can’t.

Without demotion, the post would reach the majority of the network. A 10% reduction has little impact; the reach remains almost the same. But a 20% reduction causes its reach to drop tenfold, and the content only reaches the poster’s immediate network. The specific numbers here are not important; the point is that the effect of demotion on reach can be unpredictable, nonlinear, and sometimes drastic.

Some Social Media Algorithms

We know relatively little about how Twitter’s For You algorithm works. For some ideas of how it might work we can look at other sites, which is what this section will do.

For this section I’ll be quoting extensively from this very long, very strong post on Understanding Social Media Recommendation Algorithms.

What is engagement on various platforms? If gamer is going to Goodhart, gamer’s got to Goodhart good.

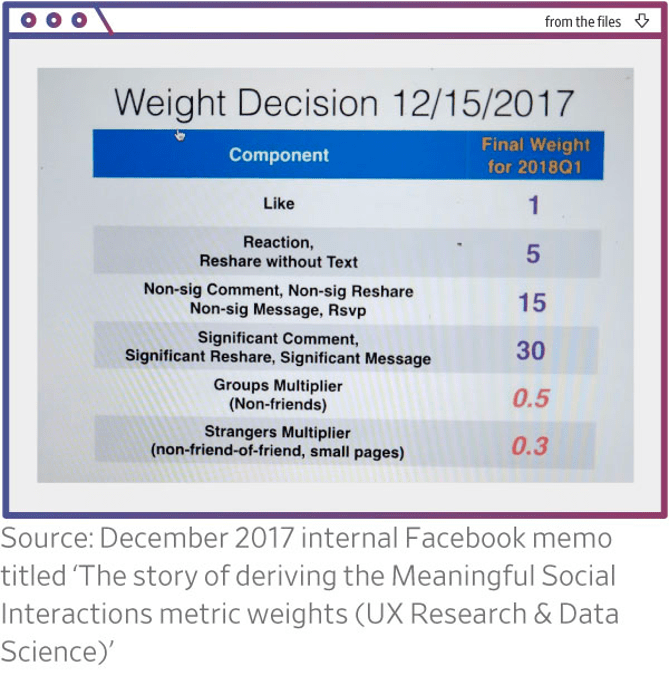

Facebook optimizes for “Meaningful Social Interactions,” a weighted average of Likes, Reactions, Reshares, and Comments.

Twitter, similarly, combines all the types of interaction that a user might have with a tweet.

YouTube optimizes for expected watch time, that is, how long the algorithm predicts the video will be watched. If a user sees a video in their recommendations and doesn’t click on it, the watch time is zero. If they click on it and hit the back button after a minute, the watch time is one minute. Before 2012, YouTube optimized for click-through rate instead, which led to clickbait thumbnails (such a sexualized imagery) becoming ubiquitous; hence the shift to watch time.

Less is known about TikTok’s algorithm than those of the other major platforms, but it appears broadly similar: a combination of liking, commenting, and play time. The documentation says that whether a video was watched to completion is a strong signal, and this factor probably gives the platform some of its uniqueness. One indirect indication of the importance of this signal is that very short videos under 15 seconds—which are more likely to be played to completion, and thus score highly—continue to dominate the platform, despite the length restriction having been removed.

Netflix originally optimized for suggesting movies that the user is likely to rate highly on a scale of one to five; this was the basis for a $1M recommender system competition, the Netflix Prize, in 2006. But now it uses a more complex approach.

Some other tidbits I found fascinating.

Platforms like Netflix and Spotify have found that explaining why a recommendation was made makes them more persuasive. They have made various modifications to their algorithms to enable this.

There’s a tradeoff between recommending content similar to what the user has engaged with in the past, which is a safe choice, and recommending new types of content so that the algorithm can learn whether the user is interested in it—and perhaps influence the user to acquire new interests. There’s a class of algorithms devoted to optimally navigating this tradeoff. TikTok is notable for its emphasis on exploration.

[From the Netflix Prize contest]: The big insight to come out of the contest was the idea of matrix factorization, which undergirded what I see as the second generation of recommendation algorithms.

I find it so weird that this came out of the contest, given how obvious it seems – I didn’t get far in the contest because I can’t code well, and I called it delta mapping, but I absolutely came up with the core algorithmic trick here. The argument is that they stopped using it because it is opaque and people need to know why they are being recommended something, but… how is this a serious issue? If we are ever going to hope to solve AI Alignment via interpretability, certainly we can solve the orders-of-magnitude-easier problem of figuring out what (most of) the matrix factors represent. This seems super easy, as in so easy that I’d bet that I could definitely do this with one good coder, given the output of the algorithm, and I could quite possibly do it with zero.

Besides, for social media, matrix factorization is a nonstarter. Netflix, at the time, had a tiny inventory of about 18,000 videos, so the algorithm was possible to compute. On a scale of billions of posts it is computationally intractable, especially considering that the algorithm has to work in real time as new posts are constantly being uploaded.

Again, no, this is totally a problem we can solve. In this case, the recommendations are opaque anyway so we don’t even need to know what the factors represent, although I suspect it would be helpful. You generate the factors and you categorize the users offline, when you’re not under time pressure. In real time, all you have to do is calculate how a given user will react to a given offering. I mean, I assume this is harder to do with limited compute than it seems but if the attitude so far is ‘this can’t be done’ then that would be why it hasn’t been done.

On the other hand, my expectation is that the thing that is actually being done is functionally similar to the old system, perhaps almost identical, so it’s fine? But while that’s a reason not to do the old thing, that’s also more of a reason to think the old thing wouldn’t be that hard?

(I am so totally done with Efficient Market Hypothesis arguments of the form ‘no, if this was doable in a useful way they would have figured out how to do it and done it.’)

If they are so hit-or-miss, how can recommendation algorithms possibly be causing all that is attributed to them? Well, even though they are imprecise at the level of individual users, they are accurate in the aggregate. Compared to network-based platforms, algorithmic platforms seem to be more effective at identifying viral content (that will resonate with a large number of people). They are also good at identifying niche content and matching it to the subset of users who may be receptive to it.

…

Behavioral expertise is useful in designing the user interfaces of apps, but there is little human knowledge or intuition about what would make for a good recommendation that goes into the design of their algorithms. The algorithms are largely limited to looking for patterns in behavioral data. They don’t have common sense.

This can lead to algorithmic absurdities: like ads featuring earwax, toenail fungus, or other disgusting imagery.

I can definitely imagine ways letting the psychiatrists tinker with the algorithm could do more harm than good. It still seems like they should be excellent at hypothesis generation, and noticing impacts that one didn’t think to measure.

Algorithms care about short-term outcomes and they care about exploration and discovery, both of which are important. Yet there is little talk of overall sentiment, over any term length, or general customer satisfaction or utility, or actually predicting customer spending behaviors in the end. Certainly there are a bunch of things I would be measuring and modeling that aren’t mentioned anywhere in this post. Is this because they don’t matter, or are impossible to usefully measure or predict? Maybe? My guess is no.

So if even, say, 0.1% of people click on gross-out ads for whatever reason—morbid curiosity?—the ad engines count that as success. They don’t see and don’t care about the people who hit the back button as soon as they see the image. This harms the publisher in addition to the user, but neither party has any much power to change things.

Really (as in with Seth and Amy)? No one has the power to change things? The website doesn’t have a slate of analytics including time spent on site and conversion rates that knows an exact time with an extension that could be tied back to the social media user and shared with the website. Really? Yeah. Not buying it. Do better.

Here’s another case of hands being thrown up when the right reaction would be the opposite.

It is debatable how much control engineers have over the effects of recommendation algorithms. My view is that they have very little. Let me illustrate with an example. In 2019, Facebook realized that viral posts were much more likely to contain misinformation or many other types of harmful content. (The correlation between virality and misinformation is also consistent with some research.) In other words, the shift to Meaningful Social Interactions had had the opposite of the intended effect: Content that provoked outrage and stoked division was gaining in reach instead. This was a key point of Frances Haugen’s testimony and has been extensively written about in the press.

Yes, that change made the problem much worse. Should you respond with ‘my choices don’t matter?’

Principle of Symmetrical Influence: If you have the power to make things much worse, you should suspect you also have the power to make them better. Proof: You can at minimum avoid accidentally (or intentionally) making things worse.

My response to the news that virality under MSI (meaningful social interactions) correlates highly with harmful content is that it’s unfortunate but also super valuable new information. I can use that.

Facebook’s response was to super-weight comments and relatively stop caring about reshares. To me that is essentially a hostile act. A reshare is an explicit statement that you want others to see it. A comment isn’t, and is often negative. So an informed user would then adapt to the new regime.

You should too. I recommend against using Facebook at all, but some people will anyway, and this applies throughout social media: If you don’t want something to go viral and there is a chance it might, don’t comment on it, even to correct it, don’t interact with it, ever. Treat it like toxic waste.

My approach would instead have been to ask what I even meant by an MSI. If a negative reaction can count as an MSI, then this isn’t a perverse result, you got what you asked for quite directly. One idea would be to use an LMM for sentiment analysis of the comment section. Another would be to see how users react on the site after seeing the post, over various time scales. There’s a lot of other ways to go about this.

I think there are two driving principles behind Facebook engineers’ thinking that explain why they’ve left themselves with so little control.

First, the system is intended to be neutral towards all content, except for policy violating or “borderline” content. To be sure, the list of types of content, users, and groups that are algorithmically demoted seems to be ever growing.

…

Ultimately, designing for neutrality ends up rewarding those who are able to hack engagement or benefit from social biases.

…

The second main driving principle is that the algorithm knows best. This principle and the neutrality principle reinforce each other. Deferring the policy (about which content to amplify) to the data means that the engineers don’t have to have a point of view about it.

The algorithm-knows-best principle means that the same optimization is applied to all types of speech: entertainment, educational information, health information, news, political speech, commercial speech, art, and more.

I mean, yes, if you want to differentiate between different types of content and different content effects it is going to be hard to do that while being indifferent between different types of content.

If you want to avoid rewarding those who exploit bias, while ruling out any way to identify or respond to that bias, that’s going to be a hard problem for you to solve.

And if you decide that you will defer all decisions ‘to the algorithm,’ which I interpret as ‘let it maximize engagement or some other X’ and you care about other thing Y, well, you just decided not to care about that, don’t come crying to me.

If you’re using the same optimization on all different kinds of speech… why? Don’t they work differently? Shouldn’t the algorithm automatically not treat them the same, whether you label this difference or not?

If users want more or less of some types of content, the thinking goes, the algorithm will deliver that. The same applies to any other way in which a human designer might try to tweak the system to make the user experience better. For example, suppose someone suggested to a Facebook engineer that posts related to the user’s job or career, posts from colleagues, etc. should have slightly higher priority during work hours, with posts about parties or entertainment prioritized during evenings or weekends.

The engineer might respond along these lines: “But who are we to make that decision? Maybe people actually secretly want to goof off during work. If so, the algorithm will let them do that. But if the policy you’re asking for is actually what users want, then the algorithm will automatically discover it.”

The level of adherence to these principles can be seen in how timid the deviations are.

The engineer’s response to this particular proposal seems wise. There is no reason to assume a particular person, or people in general, will prefer more work stuff or personal stuff during work hours, so you shouldn’t guess for them. It still makes sense to ensure the algorithm has the power to make the differentiation, if it can’t easily do that no reason to assume the algorithm can ‘automatically’ do the work.

The training data was generated by surveying users. Facebook found that posts with higher reach were more likely to be “bad for the world,” so it wanted to algorithmically demote them. The first model that it built successfully suppressed objectionable content but led to a decrease in how often users opened the app—incidentally, an example of the ills of engagement optimization. So it deployed a tweaked, weaker model.

There are some things I would try before falling back on weaker, but I certainly understand why you might choose to be bad for the world instead of bad for Facebook. Or you could realize that this heavily implies that Facebook itself is bad for the world, and people go there for bad reasons – people wanted to see things they themselves thought were harmful and wouldn’t check otherwise.

I find these things fascinating. In another life, they’re what I have long worked on. In general, what I see seems to barely scratch the surface of what is possible, and seems like a distinct lack of curiosity all around.

The central theme seems to be that when you use implicit measures and observe data on the order of seconds, you have tons and tons of training data. You can get good. Whereas if you rely on explicit feedback (which people largely don’t want to give you anyway) and longer term effects, you have less data. So we fall back on the short term more and more, until you get TikTok, and the implicit more and more so anything more deliberate loses out. The long term impacts aren’t measured so they aren’t managed.

Of course, platforms pay close attention to metrics like retention and churn, but countless changes are made over a period of six months, and without an A/B test, there’s no good way to tell which changes were responsible for users quitting.

For example, Facebook found that showing more notifications increased engagement in the short term but had the opposite effect over a period of a year.

I do realize these are tricky problems to solve, yet these platforms have massive user counts over periods of years. It does not seem so crazy to think there is enough data, or failing that, enough time to run longer term experiments.

How to Live With Twitter’s Algorithm as a Reader?

If you are following my How to Best Use Twitter advice, you are currently never using the algorithmic For You feed. Instead, you stick entirely to the Following feed, which won’t change, or you use Lists and Tweetdeck.

In that case, none of this matters that much for you. At least for now.

A form of the algorithmic feed will still poke its head out from the bottom of the page sometimes, and obnoxiously will often include a moving picture, but you can mostly ignore that. That form also is clearly very very different than the current For You feed. The extra bottom-page stuff is all super-viral offerings, which is a completely different set of posts.

How you interact with content still matters for other people. Your likes and retweets and replies even expansions will impact engagement and virality patterns for 80% of everyone on the platform. That means you want to take such actions more aggressively when you want something to have more impressions and virality, and be more careful to avoid it when you want that thing to have less, even more so than before.

Those interactions will (I think) also have an impact on which replies you see. Not as big a deal, still nothing to sneeze at. Replies can be quite valuable.

For a long time I have had a policy that I do not use likes on Twitter. In a world in which someone can be attacked for even liking a Tweet, I figured, and where people might otherwise attempt to draw inference from which Tweets you did or did not like, it was better not to play such games.

Now I no longer feel I can continue that policy. If I want the world to see more of something, I’ll need to click the like button, as a silent mini-retweet. So starting today, I’m going to switch to that policy. That’s what a like from me means, a vote for more impressions.

It also means I’d appreciate the same in return. We all need all the algorithmic boosts we can get. And I’ll practice at least some reciprocity. I don’t love the new equilibrium, but I’ve definitely solved for it.

If you dare engage with or care about the contents of the algorithmic feed, what then?

Then you need to double down on deliberate engagement.

Mindless scrolling means you can’t (or, rather, can’t safely, and shouldn’t) do mindless scrolling. Big algorithm is watching you. Whereas if you control the system, you have to do work to control it, but once you do you can relax.

You need to be ruthless with even expanding a Tweet, let alone liking or retweeting or responding. Think carefully before you do that. Do you want your For You feed to have more of this? Do you want others to see this more, and this kind of thing more?

The flip side applies as well. If you want to see more of a type of thing, you’ll need to teach the algorithm that.

I’d also hope experiments (involving AI?) are being run, to see what sends what messages, and what to keep an eye out for. I see a remarkable lack of this type of experiment being run. I understand why the creators of such systems are loathe to reveal their inner workings, and why most people choose not to care, but enough of us still care to justify the experiments.

The other possibility that is you could, in theory anyway, move the people you most care about onto lists, follow almost no one, and then move to a hybrid approach where you use For You for exploration, and combine that with your lists. Perhaps that is actually a very good strategy. It does seem like a lot of overhead work.

What will this do to new user acquisition?

Damion Schubert argues it will go terribly, because instead of being offered Steven King, Neil Gaiman and William Shatner you’ll only be offered blue check marks, which means a bunch of MAGAs.

At the time, I believe he was under the old understanding, where King, Gaiman and Shatner would be unavailable on For You even if you followed them. That’s been fixed now. So the algorithm is free to offer those accounts to you, if it wants, and of course you can use the Following tab if you prefer.

Another question is, why should we assume that only MAGAs will pay up? Twitter has always been very very blue in its politics. Let’s say 5% of active users pay. That still leaves a ton of people to suggest that are normal celebrities, that lean blue, that won’t drive you away.

I have heard of people who hate MAGA complaining about all the MAGA stuff in their For You timelines. When I tested my own For You, it had zero MAGA in it, nothing remotely close. My guess is that those people are tricked into interacting with such content, so the algorithm feeds them more. The solution is obvious.

Finally, we talk about King and Gaiman and Shatner because they are beloved creators who have already hit it big and are happy to stand up for the righteous principle of not paying $8 for their social media platform and that if anything Twitter should be paying them.

Whereas if you are a remotely normal content creator, someone who is trying to make a living, and you won’t pay the $8, what are you thinking? This is peanuts. Pay the man his money. Or you can, as some will, cut off your nose to spite your face. Many will pay.

Thus, I expect at most a modest decline in the ‘who to follow’ new user experience.

My bigger concern would be that most new users won’t pay. So they won’t be able to vote in polls, and their posts will be ineligible for the For You tab (since they won’t have followers yet), which means their reach and ability to build up their account and get off the ground will be extremely limited. How are they going to get sufficient engagement to keep themselves on the platform, let alone enough to justify paying money?

If you are joining Twitter the way you would join TikTok, as a consumer of a feed, then this mostly seems fine. You don’t need followers or impressions for that. Then, perhaps, you can slowly become someone who replies or posts, or not.

If you are joining Twitter to offer content, on the other hand, perhaps you do pay right away. That puts you in the 5% that pay, and suddenly your content is going to get at least some shot. Seems like a quality product?

If they are joining Twitter to follow their friends, the Following tab is still there.

It’s going to complicate matters a little, there will be greater friction, but I don’t expect things to be too bad. I think most people who join Twitter do so mainly as content consumers first, not creators.

How to Live With Twitter’s Algorithm as a Creator?

First off, if you’re not only talking to friends that you know?

That will be $8.

I understand the urge not to encourage the bastard. I do. I know you think social media should be free, or that the bastard should be paying you, the creator, rather than the other way around.

You love that This Website is Free. I love free too. We are all addicted to free, and feel entitled to free, in a way that is actually pretty toxic.

You might be tempted to say, my followers will still see my stuff.

Doesn’t matter. Think on the margin. The $8 is chump change given the amount of reach you get, or the amount of value you get from Twitter.

If you often spend time on Twitter and sometimes produce content, and you don’t think Twitter is worth your $8, then what is the chance it is worth at least zero dollars? What is the chance it isn’t worth a lot less than negative $8?

Very low. If on reflection you don’t think the $8 is Worth It, ask whether your time is Worth It. Consider that asking this question may have done you a big favor.

Yes, some people will judge you for paying. Whatever. Impact is minimal. If you actually worry about this, you’re hanging out with the wrong crowd.

The only exception is if you actively want to not appear in feeds of people unless that person seeks you out, as Mathew Yglesias (another account that has plenty of followers) suggests he prefers. In which case, not paying seems fine.

All right, that’s out of the way. You have paid. Now what?

You are producing content for two distinct groups of people. There are those who are following you and will see everything you post, or at least quite a lot of it via the For You tab. Then there are those who will only see your stuff if it appears on the algorithmic feed.

For the Following group including lists, and anyone you might tag and reach via notifications, nothing has changed, except that you no longer have ‘partial’ following people to complement them.

For the For You group, you now have less competition, which should help your reach and the relative importance of this group. You will be judged largely on an algorithmic basis, so this means more attention to virality especially at the margins.

Direct interventions to boost virality seem more worthwhile now. So it makes more sense to ‘punch up’ one’s taglines, to push secondary detail into threaded posts, and do other similar things. This effect, like all the others I note, is moderated now that we know who you follow will still matter, but the effect is still there.

You can likely worry less about having a focus. If you post about multiple topics, for different groups, the algorithm should be able to figure that out. I plan to be post at least somewhat more often about games and sports in the new world.

Posting more seems like it will be more likely to get rewarded, unless the algorithm is looking closely at your average numbers when deciding how you get treated. You don’t want people to mute or block you, or learn that you’re mostly boring, but familiar faces should generally be an advantage, and you miss 100% of the virality you don’t post.

The weird question is on how much it matters to build your brand. It looked like building your brand was about to become not so important. Instead, perhaps it is more important than ever? On TikTok as I understand it, each video stands completely on its own, your brand does not much matter, if you make videos professionally it is because you got good. The new Twitter was going to be like that, we thought, and now it won’t be, although I’d expect an algorithmic move towards that on the margin.

Did Twitter Just Kill Polls?

It certainly does look that way.

We know most people won’t pay. Most people don’t pay for anything.

So what happens to polls when sample sizes drop 90%?

When I send out a poll I typically get a few hundred responses. Not only would blue-only responses warp the data even further than it is already warped, they would severely reduce sample size.

There are alternatives. One could instead try to link outside to another way one could run a poll. For example, as illustrated below, Substack enables this, except it requires a subscription to vote, and also the click is a major trivial inconvenience, so you lose 90% anyway.

Loading…

Loading…

There is the possibility that this will improve polls that can still get sufficient sample size. I am deeply skeptical.

What Happens to Twitter Now?

Twitter Blue subscriptions should jump modestly, at least for a time. I don’t expect the full more-than-doubling that we would have gotten if you were facing complete exile from the For You tab.

My guess is revenue will on net go up even with only a modest bump in blue subscriptions. Usually a lot more people say they will quit or reduce time spent on the site than actually do when things change.

Previously I was worried the changes would be a major negative for many For You feed users. Now I am not convinced there will be substantial net impact for them. It should be fine. There will be some increased issues with elitist or exclusionary vibes. The negative impact should mostly fall on the creator side, for those who are not committed enough to simply pay up, or whose brands prevent them from paying.

I don’t see much other upside to the changes and restrictions, aside from revenue. I expect the upside of limiting the reach of bots and spam to have almost zero impact on user experience. When I see bots and spam, it is almost always via DMs and tags. As I noted earlier on, which it is likely the bot and spam problems will continue to accelerate, there were other less impactful ways to respond to that threat. I believe that those responses could have kept things at roughly their current equilibrium for at least a while, potentially indefinitely.

Is there danger of collapse, an existential risk to Twitter? There is almost never zero risk of this. Network effects are robust until they are fragile. A cascade of declining value could definitely happen. Once lost they usually cannot be restored.

However, with the retreat on followed accounts, I don’t see enough here to pose much of a threat. Even before that, I wasn’t all that worried.

The reason I was not that worried is that I notice that a lot of people have been saying that this was bound to happen Real Soon Now ever since Musk bought Twitter, yet Twitter has stayed (as far as I can tell) roughly the same in the ways that matter. They said the site could not possibly survive, was collapsing by the day. They were wrong. They said people would leave in droves. They were mostly wrong and the ones that were going to leave have left. We have gotten strong evidence that Twitter is more robust than many expected.

Thus, I didn’t expect a dramatic drop in platform use even with the draconian version of the new rule. I certainly don’t expect anything too bad now, with the polls being the bigger issue of concern. If it turns out to be a huge deal, there are clear and easy fixes.

I also notice that with the rapid advancements in AI, Twitter is more important than ever. Speed premium matters more, and there are more things that Twitter is perfect for talking about. There is even the promise that AI could in the future assist in curation of your feed. That seems like a promising area of exploration, with the main risk not being that one couldn’t build a valuable product, but whether or not you would be permitted to offer that product legally. If you could de-risk legal issues, sky is the limit.

Right now AI is a complement to Twitter. One potential reason to be skeptical is that perhaps AI could become a substitute for Twitter, as a real-time processor of lots of information feeds that gives you what you need to know sufficiently well that you no longer need to use Twitter for anything non-local.

We shall see. If Twitter as it exists mostly goes away, I will need to figure out new information flows. That would suck short term, but perhaps could perhaps be quite a good thing.

15% (1162/7704)

Huh. It was much higher initially. I will fix.

I just want to highlight something- the original iteration made some MASSIVE mistakes. In less than a few hours, Zvi somehow found out about the mistakes, and immediately took down the article and replaced it with a heavily repaired version. It still makes some big mistakes, most of which are basically impossible for a generalist blogger not to make. But this level of competence is still above and beyond the standards of open source intelligence. I’m very glad that this research was done.

Um, false?

The risk of getting hooked on twitter’s news feed for more than >2 hours per day is much more net-negative than ±8 USD. In fact, sinking in $8 makes you feel invested, same as the $20/m GPT4 fee, and then the news feed throws you bones at the exact frequency that keeps you coming back (including making a strong first impression). It’s gacha-game-level social engineering. If you lose the loser, you lose 100% of what you could have done to them or gotten out of them, making user retention the top priority. This is the case, even if you ignore the fact that there are competing platforms, all racing to the bottom to strategically hook/harvest any users/market share that your system leaves vulnerable.

There is an easy fix. It is to make a google doc, with a list of links to the user page of all the facebook and twitter accounts that are worth looking at, and bookmark that google doc so you can check all of them once a day. No news feeds, and you’re missing nothing. You can also click the “replies” tab on the user page to see what they’re talking about. It’s such an easy and superior fix.

What’s the difference between the Google Doc and a Twitter List with those accounts on it?

I can see the weird border case where the $8 gets you invested in a bad way but $0 makes you consume in a good way, I guess, but it’s weird. Mostly sounds like you very much agree on the danger of much worse than -$8.

Also, you say there are still a bunch of mistakes. Even if it’s effectively too late to fix them for the post (almost all readers are within the first 48 hours) I’d like to at least fix my understanding, what else did I still get wrong, to extent you know?

I don’t know what a Twitter List is, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised to see it containing some kind of trap to steer the user into a news feed.

Social media/enforced addiction stuff is not only something that I avoid talking about publicly, but it’s also something that I personally must not change the probability of anyone blogging about it. I will get back to you on this once I’ve gone over more of your research, but what I was thinking of would have to be some kind of research contracting for Balsa, that comes with notoriously difficult-to-hash-out assurances of not going public about specific domains of information.

Fair enough.

A twitter list is literally: You create it (or use someone else’s) and if you load it (e.g. https://twitter.com/i/lists/83102521) you get the people on the lists in reverse chronological order and nothing else (or you can use Tweetdeck). Doesn’t seem to have traps.

Graph algorithms are notoriously difficult to scale. It is very much a problem on the bleeding edge of technology.

Edit: Also, Zvi is underestimating how smart he is relative to the general population. I would predict with high confidence that he could replace me at my software engineering job with less than two weeks of training.

Before GPT-4 I would have said I’d run that experiment and I definitely couldn’t.

With it? Maybe.