I still disagree with that.

philh

I’ve written about this here. Bottom line is, if you actually value money linearly (you don’t) you should not bet according to the Kelly criterion.

I think we’re disagreeing about terminology here, not anything substantive, so I mostly feel like shrug. But that feels to me like you’re noticing the framework is deficient, stepping outside it, figuring out what’s going on, making some adjustment, and then stepping back in.

I don’t think you can explain why you made that adjustment from inside the framework. Like, how do you explain “multiple correlated bets are similar to one bigger bet” in a framework where

Bets are offered one at a time and resolved instantly

The bets you get offered don’t depend on previous history

?

This is a synonym for “if money compounds and you want more of it at lower risk”.

No it’s not. In the real world, money compounds and I want more of it at lower risk. Also, in the real world, “utility = log($)” is false: I do not have a utility function, and if I did it would not be purely a function of money.

Like I don’t expect to miss stuff i really wanted to see on LW, reading the titles of most posts isn’t hard

It’s hard for me! I had to give up on trying.

The problem is that if I read the titles of most posts, I end up wanting to read the contents of a significant minority of posts, too many for me to actually read.

Ah, my “what do you mean” may have been unclear. I think you took it as, like, “what is the thing that Kelly instructs?” But what I meant is “why do you mean when you say that Kelly instructs this?” Like, what is this “Kelly” and why do we care what it says?

That said, I do agree this is a broadly reasonable thing to be doing. I just wouldn’t use the word “Kelly”, I’d talk about “maximizing expected log money”.

But it’s not what you’re doing in the post. In the post, you say “this is how to mathematically determine if you should buy insurance”. But the formula you give assumes bets come one at a time, even though that doesn’t describe insurance.

The probability should be given as 0.03 -- that might reduce your confusion!

Aha! Yes, that explains a lot.

I’m now curious if there’s any meaning to the result I got. Like, “how much should I pay to insure against an event that happens with 300% probability” is a wrong question. But if we take the Kelly formula and plug in 300% for the probability we get some answer, and I’m wondering if that answer has any meaning.

I disagree. Kelly instructs us to choose the course of action that maximises log-wealth in period t+1 assuming a particular joint distribution of outcomes. This course of action can by all means be a complicated portfolio of simultaneous bets.

But when simultaneous bets are possible, the way to maximize expected log wealth won’t generally be “bet the same amounts you would have done if the bets had come one at a time” (that’s not even well specified as written), so you won’t be using the Kelly formula.

(You can argue that this is still, somehow, Kelly. But then I’d ask “what do you mean when you say this is what Kelly instructs? Is this different from simply maximizing expected log wealth? If not, why are we talking about Kelly at all instead of talking about expected log wealth?”)

It’s not just that “the insurance calculator does not offer you the interface” to handle simultaneous bets. You claim that there’s a specific mathematical relationship we can use to determine if insurance is worth it; and then you write down a mathematical formula and say that insurance is worth it if the result is positive. But this is the wrong formula to use when bets are offered simultaneously, which in the case of insurance they are.

This is where reinsurance and other non-traditional instruments of risk trading enter the picture.

I don’t think so? Like, in real world insurance they’re obviously important. (As I understand it, another important factor in some jurisdictions is “governments subsidize flood insurance.”) But the point I was making, that I stand behind, is

Correlated risk is important in insurance, both in theory and practice

If you talk about insurance in a Kelly framework you won’t be able to handle correlated risk.

If one donates one’s winnings then one’s bets no longer compound and the expected profit is a better guide then expected log wealth—we agree.

(This isn’t a point I was trying to make and I tentatively disagree with it, but probably not worth going into.)

Whether or not to get insurance should have nothing to do with what makes one sleep – again, it is a mathematical decision with a correct answer.

I’m not sure how far in your cheek your tongue was, but I claim this is obviously wrong and I can elaborate if you weren’t kidding.

I’m confused by the calculator. I enter wealth 10,000; premium 5,000; probability 3; cost 2,500; and deductible 0. I think that means: I should pay $5000 to get insurance. 97% of the time, it doesn’t pay out and I’m down $5000. 3% of the time, a bad thing happens, and instead of paying $2500 I instead pay $0, but I’m still down $2500. That’s clearly not right. (I should never put more than 3% of my net worth on a bet that pays out 3% of the time, according to Kelly.) Not sure if the calculator is wrong or I misunderstand these numbers.

Kelly is derived under a framework that assumes bets are offered one at a time. With insurance, some of my wealth is tied up for a period of time. That changes which bets I should accept. For small fractions of my net worth and small numbers of bets that’s probably not a big deal, but I think it’s at least worth acknowledging. (This is the only attempt I’m aware of to add simultaneous bets to the Kelly framework, and I haven’t read it closely enough to understand it. But there might be others.)

There’s a related practical problem that a significant fraction of my wealth is in pensions that I’m not allowed to access for 30+ years. That’s going to affect what bets I can take, and what bets I ought to take.

The reason all this works is that the insurance company has way more money than we do. …

I hadn’t thought of it this way before, but it feels like a useful framing.

But I do note that, there are theoretical reasons to expect flood insurance to be harder to get than fire insurance. If you get caught in a flood your whole neighborhood probably does too, but if your house catches fire it’s likely just you and maybe a handful of others. I think you need to go outside the Kelly framework to explain this.

I have a hobby horse that I think people misunderstand the justifications for Kelly, and my sense is that you do too (though I haven’t read your more detailed article about it), but it’s not really relevant to this article.

I think the thesis is not “honesty reduces predictability” but “certain formalities, which preclude honesty, increase predictability”.

I kinda like this post, and I think it’s pointing at something worth keeping in mind. But I don’t think the thesis is very clear or very well argued, and I currently have it at −1 in the 2023 review.

Some concrete things.

There are lots of forms of social grace, and it’s not clear which ones are included. Surely “getting on the train without waiting for others to disembark first” isn’t an epistemic virtue. I’d normally think of “distinguishing between map and territory” as an epistemic virtue but not particularly a social grace, but the last two paragraphs make me think that’s intended to be covered. Is “when I grew up, weaboo wasn’t particularly offensive, and I know it’s now considered a slur, but eh, I don’t feel like trying to change my vocabulary” an epistemic virtue?

Perhaps the claim is only meant to be that lack of “concealing or obfuscating information that someone would prefer not to be revealed” is an epistemic virtue? Then the map/territory stuff seems out of place, but the core claim seems much more defensible.

“Idealized honest Bayesian reasoners would not have social graces—and therefore, humans trying to imitate idealized honest Bayesian reasoners will tend to bump up against (or smash right through) the bare minimum of social grace.” Let’s limit this to the social graces that are epistemically harmful. Still, I don’t see how this follows.

Idealized honest Bayesian reasoners wouldn’t need to stop and pause to think, but a human trying to imitate one will need to do that. A human getting closer in some respects to an idealized honest Bayesian reasoner might need to spend more time thinking.

And, where does “bare minimum” come from? Why will these humans do approximately-none-at-all of the thing, rather than merely less-than-maximum of it?

I do think there’s something awkward about humans-imitating-X, in pursuit of goal Y that X is very good at, doing something that X doesn’t do because it would be harmful to Y. But it’s much weaker than claimed.

There’s a claim that “distinguishing between the map and the territory” is distracting, but as I note here it’s not backed up.

I note that near the end we have: “If the post looks lousy, say it looks lousy. If it looks good, say it looks good.” But of course “looks” is in the map. The Feynman in the anecdote seems to have been following a different algorithm: “if the post looks [in Feynman’s map, which it’s unclear if he realizes is different from the territory] lousy, say it’s lousy. If it looks [...] good, say it’s good.”

Vaniver and Raemon point out something along the lines of “social grace helps institutions perservere”. Zack says he’s focusing on individual practice rather than institution-building. But both his anecdotes involve conversations. It seems that Feynman’s lack of social grace was good for Bohr’s epistemics… but that’s no help for Feynman’s individual practice. Bohr appreciating Feynman’s lack of social grace seems to have been good for Feynman’s ability-to-get-close-to-Bohr, which itself seems good for Feynman’s epistemics, but that’s quite different.

Oh, elsewhere Zack says “The thesis of the post is that people who are trying to maximize the accuracy of shared maps are going to end up being socially ungraceful sometimes”, which doesn’t sound like it’s focusing on individual practice?

Hypothesis: when Zack wrote this post, it wasn’t very clear to himself what he was trying to focus on.

Man, this review kinda feels like… I can imagine myself looking back at it two years later and being like “oh geez that wasn’t a serious attempt to actually engage with the post, it was just point scoring”. I don’t think that’s what’s happening, and that’s just pattern matching on the structure or something? But I also think that if it was, it wouldn’t necessarily feel like it to me now?

It also feels like I could improve it if I spent a few more hours on it and re-read the comments in more detail, and I do expect that’s true.

In any case, I’m pretty sure both [the LW review process] and [Zack specifically] prefer me to publish it.

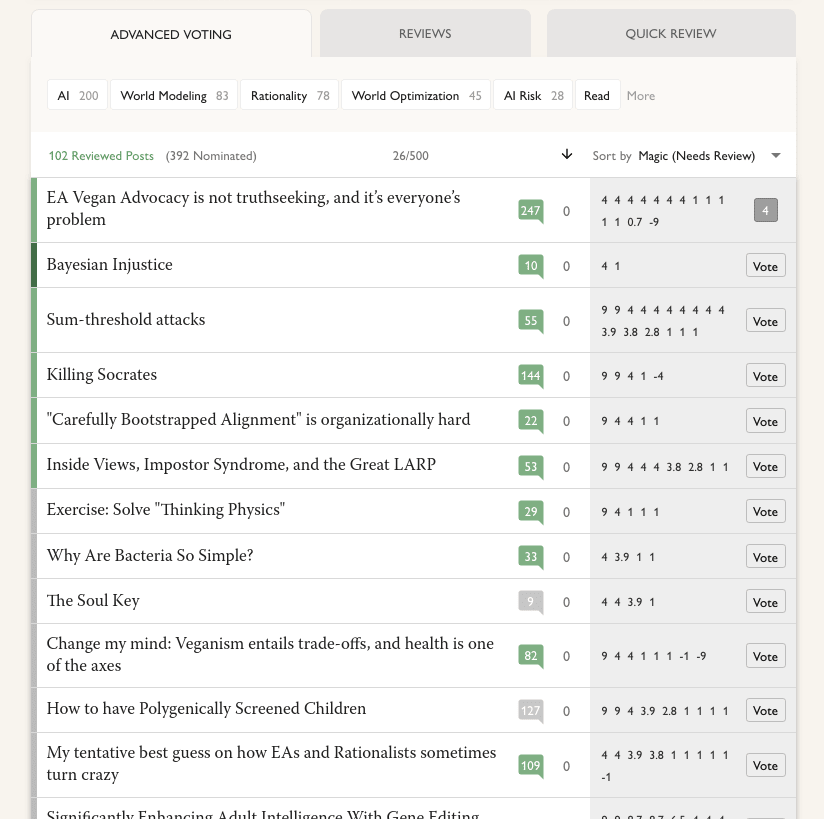

Ooh, I didn’t see the read filter. (I think I’d have been more likely to if that were separated from the tabs. Maybe like,

[Read] | [AI 200] [World Modeling 83] [Rationality 78] ....) With that off it’s up to 392 nominated, though still neither of the ones mentioned. Quick review is now down to 193, my current guess is that’s “posts that got through to this phase that haven’t been reviewed yet”?Screenshot with the filter off:

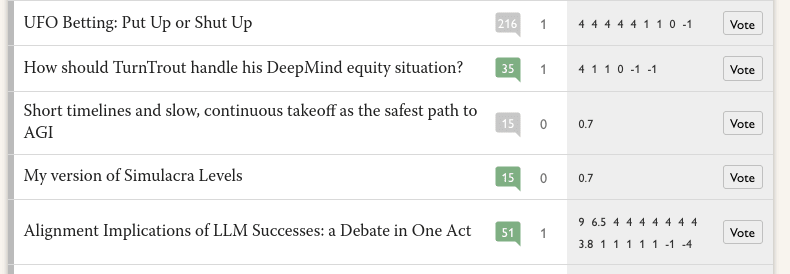

and some that only have one positive review:

Btw, I’m kinda confused by the current review page. A tooltip on advanced voting says

54 have received at least one Nomination Vote

Posts need at least 2 Nomination Votes to proceed to the Review Phase

And indeed there are 54 posts listed and they all have at least one positive vote. But I’m pretty sure this and this both had at least one (probably exactly one) positive vote at the end of the nomination phase and they aren’t listed.

Guess: this is actually listing posts which had at least two positive votes at the end of the nomination phase; the posts with only one right now had two at the time?

...but since I started writing this comment, the 54 has gone up to 56, so there must be some way for posts to join it, but I don’t have a guess what it would be.

And then the quick review tab lists 194 posts. I’m not sure what the criteria for being included on it is. It seems I can review and vote on each of them, where I can’t do that for the two previous posts, so again there must be some criteria but I don’t have a guess what.

I think it’s good that this post was written, shared to LessWrong, and got a bunch of karma. And (though I haven’t fully re-read it) it seems like the author was careful to distinguish observation from inference and to include details in defense of Ziz when relevant. I appreciate that.

I don’t think it’s a good fit for the 2023 review. Unless Ziz gets back in the news, there’s not much reason for someone in 2025 or later to be reading this.

If I was going to recommend it, I think the reason would be some combination of

This is a good example of investigative journalism, and valuable to read as such.

It’s a good case study of a certain type of person that it’s important to remember exists.

But I don’t think it stands out as a case study (it’s not trying to answer questions like “how did this person become Ziz”), and I weakly guess it doesn’t stand out as investigative journalism either. E.g. when I’m thinking on these axes, TracingWoodgrains on David Gerard feels like the kind of thing I’d recommend above this.

Which, to be clear, not a slight on this post! I think it does what it wanted to do very well, and what it wants to do is valuable, it’s just not a kind of thing that I think the 2023 review is looking to reward.

Self review: I really like this post. Combined with the previous one (from 2022), it feels to me like “lots of people are confused about Kelly betting and linear/log utility of money, and this deconfuses the issue using arguments I hadn’t seen before (and still haven’t seen elsewhere)”. It feels like small-but-real intellectual progress. It still feels right to me, and I still point people at this when I want to explain how I think about Kelly.

That’s my inside view. I don’t know how to square that with the relative lack of attention the post got, and it feels weird to be writing it given that fact, but oh well. There are various stories I could tell: maybe people were less confused than I thought; maybe my explanation is unclear; maybe I’m still wrong on the object level; maybe people just don’t care very much; maybe it just happened not to get seen.

If I were writing this today, my guess is:

It’s worth combining the two posts into one.

The rank optimization stuff is fine to cut, given that I tentatively propose it in one post and then in the next say “probably not very useful”. Maybe have a separate post for exploring it. No need to go into depth on “extending Kelly outside its original domain”.

The charity stuff might also be fine to cut. At any rate it’s not a focus.

Someone sent me an example function satisfying the “I’m pretty sure yes” criteria, so that can be included.

Not sure if this belongs in the same place, but I’d still like to explore more the “what if your utility function is such that maximizing expected utility at time doesn’t maximize expected utility at time ?” thing. (I thought I wrote this in the post somewhere, but can’t see it: the way I’d explore this is from the perspective of “a utility function is isomorphic to a description of betting preferences that satisfy certain constraints, so when we talk about a utility function like that, what betting preferences are we talking about?” Feels like the kind of thing someone’s likely already explored, but I haven’t seen it if so.)

(At least in the UK, numbers starting 077009 are never assigned. So I’ve memorized a fake phone number that looks real, that I sometimes give out with no risk of accidentally giving a real phone number.)

Okay. Make it £5k from me (currently ~$6350), that seems like it’ll make it more likely to happen.

If you can get it set up before March, I’ll donate at least £2000.

(Though, um. I should say that at least one time I’ve been told “the way to donate with gift said is to set up an account with X, tell them to send the money to Y, and Y will pass it on to us”, and the first step in the chain there had very high transaction fees and I think might have involved sending an email… historical precedent suggests that if that’s the process for me to donate to lightcone, it might not happen.)

Do you know what rough volume you’d need to make it worthwhile?

London rationalish meetup @ Arkhipov

I don’t know anything about the card. I haven’t re-read the post, but I think the point I was making was “you haven’t successfully argued that this is good cost-benefit”, not “I claim that this is bad cost-benefit”. Another possibility is that I was just pointing out that the specific quoted paragraph had an implied bad argument, but I didn’t think it said much about the post overall.

Here’s a puzzle about this that took me a while.

When you know the terms of the bet (what probability of winning, and what payoff is offered), the Kelly criterion spits out a fraction of your bankroll to wager. That doesn’t support the result “a poor person should want to take one side, while a rich person should want to take the other”.

So what’s going on here?

Not a correct answer: “you don’t get to choose how much to wager. The payoffs on each side are fixed, you either pay in or you don’t.” True but doesn’t solve the problem. It might be that for one party, the stakes offered are higher than the optimal amount and for the other they’re lower. It might be that one party decides they don’t want to take the bet because of that. But the parties won’t decide to take opposite sides of it.

Let’s be concrete. Stick with one bad outcome. Insurance costs $600, and there’s a 1⁄3 chance of paying out $2000. Turning this into a bet is kind of subtle. At first I assumed that meant you’re staking $600 for a 1⁄3 chance of winning… $1400? $2000? But neither of those is right.

Case by case. If you take the insurance, then 2⁄3 of the time nothing happens and you just lose $600. 1⁄3 of the time the insurance kicks in, and you’re still out $600.

If you don’t take the insurance, then 2⁄3 of the time nothing happens and you have $0. 1⁄3 of the time something goes wrong and you’re out $2000.

So the baseline is taking insurance. The bet being offered is that you can not take it. You can put up stakes of $2000 for a 2⁄3 chance of winning $600 (plus your $2000 back).

Now from the insurance company’s perspective. The baseline and the bet are swapped: if they don’t offer you insurance, then nothing happens to their bankroll. The bet is when you do take insurance.

If they offer it and you accept, then 2⁄3 of the time they’re up $600 and 1⁄3 of the time they’re out $1400. So they wager $1400 for a 2⁄3 chance of winning $600 (plus their $1400 back).

So them offering insurance and you accepting it isn’t simply modeled as “two parties taking opposite sides of a bet”.