Here’s part of a comment I got on my housing coalitions post:

I consider it extremely unlikely you have found renters with the expectation of rent going down. Assuming they want to live in a well maintained building, I consider unlikely they even desire it, once they think about it. What renters hope for in general is increases that are less than their increases in income. Landlords mostly do expect that rents will go up, but the magnitude of their expectations matters, many have the same expectations as renters for moderate increases. Others will have short term/transactional thinking and will want to charge what the market will bear.

This seems worth being explicit about: when I talk about how I think rents should be lower, I really mean lower. I’m not trying to say that it’s ok if rent keeps rising as long as incomes rise faster, but that rents should go down.

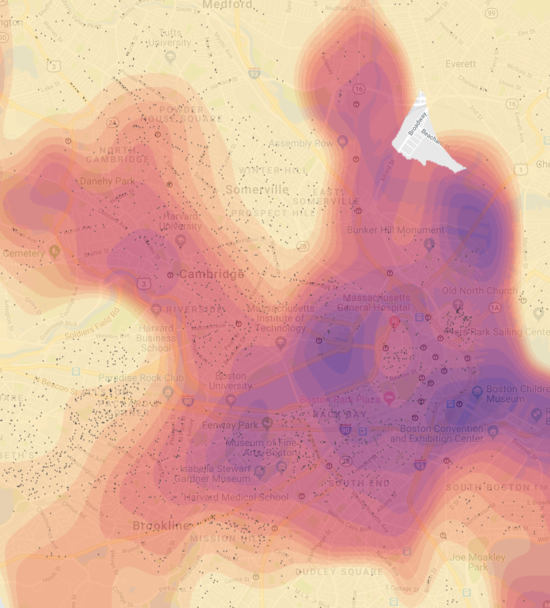

Here are Boston rents in June 2011:

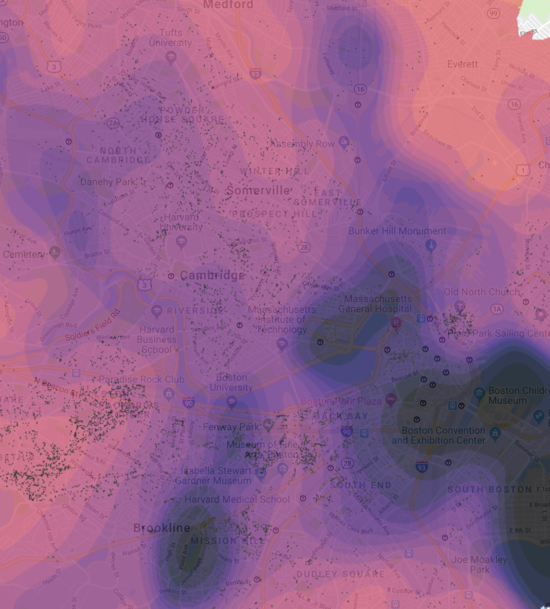

And in June 2019:

These are on the same scale, though not adjusted for inflation (13% from 2011-06 to 2019-06).

In 2011 a two-bedroom apartment in my part of Somerville would have gone for $1800/month, or $2050/month in 2019 dollars. In 2019, it would be $3000/month. Compared to 13% inflation we have 67% higher rents.

Another way to look at this is that for what you would pay now for an apartment a ten-minute walk from Davis would, in 2011, have covered an apartment a ten-minute walk from Park St. And what you would have been paying for a Harvard Sq apartment in 2011 wouldn’t get you an East Arlington apartment today.

These large increases have been a windfall for landlords. Property taxes haven’t risen much, upkeep is similar, but because demand has grown so much without supply being permitted to rise to meet it the market rent is much higher. If we build enough new housing that rents fall to 2011 levels, landlords will make less money than they had been hoping, but they’ll still be able to afford to keep up their properties.

I’ll support pretty much any project that builds more bedrooms: market rate, affordable, public, transitional. Rents are so high that all of these would still be worth building and maintaining even if everyone could see were were building enough housing that rents would fall next year to 2011 levels.

As a homeowner and a landlord, I know that this means I would get less in rent and I’m ok with that. I value a healthy community that people can afford to live in far more than a market that pays me a lot of money for being lucky enough to have bought a two-family at a good time.

I’d think that at some point before now, the super-high profits to be made from renting apartments would create political pressure to allow building more housing—after all, developers want to get more of that lovely profit.

But, it seems, no.

Same thing (even worse) has happened in the Bay Area—insane rents, yet no political will to permit building more housing.

Seems strange.

CA did just pass AB 68 + SB 13 + AB 881, which requires municipalities to allow people with single family homes to build up to two accessory dwelling units: https://carlaef.org/2019/10/09/how-to-make-your-home-a-triplex/

What are some (recent?) historical cases of urban land decreasing in price?

My current model is that this can’t really happen, because land owners have something that a lot of people gravely need, will pay basically anything to get, and until we implement a radically different civic mechanism for allocating urban land, urban life is generally going to stay close to the worst that people will tolerate rather than approaching the best that the market can provide.

The first city that came to my mind was Tokyo. I looked it up and the urban land prices decreased from 885k in 2009 yen per square meter to 758k yen per square meter in 2012. Prices also fell in Tokyo after the bust in 1992.

In completely unrelated matters, Tokyo is also the city without zoning laws...

Urban land doesn’t need to decrease in price, just urban housing. If you allow building up then it’s profitable to keep building units even as their rent falls.

Recent historical cases of urban land decreasing in price aren’t ones to emulate; they’re cases like Detroit where a city has become dramatically less desirable over time due to an industry dying. But Seattle has recently built enough new housing that they’ve seen a small decrease in rents: https://www.oregonlive.com/business/2019/01/apartment-rents-dropping-in-seattle-landlords-compete-for-tenants-as-market-cools.html

If you build more units, more people will move into the city. The equlibrium is one in which the population is on aggregate paying through the nose, one way or another. I don’t think there’s a good solution that doesn’t require a change in the economic system.

At least with the present immigration laws there’s a limit of how many people could move to a city. The bay area has a population density of 335/km2 while Manila has one of 20,785/km2. If you increase the density of the bay area to that of Manila you could house every US citizen in it.

If you grant that some people actually want to live in other cities like Boston, there’s enough city space for people to live in even without having to go to the density of a place like Manila.

You just have to be serious about cities needing much more density and you can fit everybody in them.

Something got garbled with “The bay area has a population density of while Manila has one of 20,785/km2 while the Bay area has one of 335/km2.”

Fixed it.

What do you mean by “on aggregate paying through the nose”? That rents will always be high?

I suppose it means that—assuming infinite flexibility of humans—as long as the life at some place is better than at other places, people will keep moving there. (Here, “better” includes quality of living, costs, job opportunities, etc.) The movement will only stop when the balance is achieved, that is, each place is equally good. Or when there are artificial barriers.

In other words, imagine Bay Area with cheap rents, and ask yourself why wouldn’t at least 5% of USA move there.

Currently the answer is: because they couldn’t afford the rent, or at least their potential income minus the rent isn’t worth moving there. There are many potential answers for the future, but many of them would also apply to people already living there, such as you. (For example: collapse of transit, or high crime.)

I would expect that getting rents down would generally let people to move from rural areas into cities, and within cities into denser downtown areas, because high rents currently keep people out. But:

Some people don’t want to live in cities. Proximity to nature, not wanting to have to worry about neighbors, liking having lots of open space, working in farming or another fundamentally rural occupation, etc.

Different industries are big in different cities. Software in SF, TV in LA, finance in NYC, commodities in Chicago, biotech in Boston, insurance in Hartford, etc. Depending on what sort of work you want to do different cities make sense. Similar patterns apply for subcultures.

Some people have strong roots and wouldn’t move just for better economic opportunity. A big reason I’m in Boston!

Cities compete, and the fastest growing cities are ones that are trying to make themselves more desirable.

So “the movement will only stop when the balance is achieved, that is, each place is equally good” doesn’t mean “everywhere is terrible” but instead “everywhere keeps getting better, for the people who decide to live there”.

Overall, though, since the Bay Area already has 2.4% of the US population, getting to 5% with lower rents sounds pretty reasonable. They would need to build better transit in the areas that became dense, but they would have the tax revenues to support it.

I mean something like: in the equilibrium, all consumer surplus is extracted by rents.

I’m saying “on aggregate”, because it might often not be the case in individual cases; landlords are not capable of doing perfect price discrimination on individual basis, only at the level of something like neighborhoods, roughly speaking (people sort themselves into neighborhoods by income, so the landlords can price-discriminate based on “how affluent a neighborhood you wanna live in”; people also want as short commutes as possible, so you can price-discriminate based on the distance to the nearest megalopolis).

This is made very complicated by the distinction between land and land improvements, i.e. the bare plot of land itself, on one hand, and the infrastructure and buldings built on top of it, on the other. When I talk about lands and rents, I talk about the former. The supply of land improvements is somewhat elastic (you can build more floors); the supply of land itself is absolutely inelastic.

I unfortunately don’t wanna go into the mechanism by which consumer surplus is actually extracted by rents, because I already spent some time thinking and writing this comment and I originally wanted to do something else with my Saturday.

Viliam hinted at the mechanism: land is a positional good, so, to quote him, “as long as the life at some place is better than at other places, people will keep moving there.”

Compare with other positional goods: e.g. all sports clubs’ profits will eventually be extracted by players and their agents, unless a league instantiates a wage cap, precisely because players are a positional good: you don’t care how good your players are, you only care how good they are in comparison to other teams’ players.

In the same vein, you don’t care where you live, you care how far you are from the center of gravity of where other people live (roughly speaking).

It seems like you are withdrawing to the motte. Very, few people rent bare plots of land. What’s rented (and what was referred to in the OP as rent) is rather floor space in apartments.

Why are you modeling land as a pure positional good, or even mostly positional? My goal isn’t to be closer to the middle of things than other people, I want to be near my friends and near my work. What’s positional about that, given that we can build up?

What exactly do you think “things” are, if not your friends and your work?

Everyone wants to be close to their friends and their work; that’s precisely the “gravity” that moses was talking about.

Right, but it doesn’t matter whether I’m closer than others (positional good) but whether I’m close enough that I can easily get between them (absolute good). If the world were a chessboard and only one person could live on each square then these would be the same, and it would turn into a positional good because of competition for desirable locations. But it isn’t, and we can build up enormously, which means lots of people can have a short commute and be near their friends.

The world population is not infinite. If somebody moves to San Francisco that means lower demand and lower rents wherever they came from (and conversely many other US cities now have housing crises caused by exiles from San Francisco). The desirable cities should be allowed to expand until there is more than enough room for everybody (yes, everybody) who wants to live in them to live in them, at which point landlords will no longer have the leverage to keep rents high.