What makes us happy and depressed?

This post is a cross-post from my personal blog.

What is this post about?

This post is the result of a long inquiry into happiness and depression and was kicked off by two other resources. The first is Luke Muehlhauser’s 2011 post How to Be Happy which convinced me that there are some aspects of happiness that you can improve. The second is the 80k podcast episode with Howie which convinced me that there are many aspects of your mental health that you have absolutely no control over. To integrate these two points into one overarching model, I tried to understand happiness and depression better and answer two simple questions.

How much control do you have over your happiness and depression?

What can you do to improve them or prevent worst-case scenarios?

DISCLAIMER: I’m not a trained professional in medicine, psychiatry, or anything alike. After listening to personal accounts of depression, I’m pretty convinced that I have never been depressed myself and that my worst periods were mostly prolonged sadness mixed with unhealthy expectation management. Thus, this post should be seen as the result of ca. 100 hours of reading, listening to personal stories and asking people who have more expertise rather than an expert review. I’m certain, I got some things wrong and missed important context, etc. If you notice such an omission, please contact me.

There are two resources I can really really recommend to learn more about depression. Firstly, Scott Alexander’s website (and his blog) and secondly the Our World in Data article on Depression by @saloni.

Summary of my results

Happiness and depression are very multifactorial. Some of the causes are easy, some are hard and some are impossible to control.

Ultimately, I find it easiest to think about the amount of control you have with an analogy. Imagine you ride on a canoe. You have control over your navigation and your stroke and can improve them easily through practice and training. You also have some control over the quality of the boat depending on your building skills and wealth. In the end, though, some people have a worse or better boat than others or face much rougher waters. These are the things you have no control over. But you can still mitigate their impact—even if you were given a bad boat, better handling reduces your chances of falling over.

For the rest of the article, I will categorize the level of control into three levels.

The first level will be called the Much Control Zone. It includes things you can immediately do or start to change that have a good chance of increasing your happiness. These include doing more exercise, sleeping better, or increasing exposure to the sun.

The second level will be called the Some Control Zone. These are things that include significant randomness but change is ultimately possible, even if it might require a lot of time and effort. They include the amount of money you earn, your job satisfaction, or where you live.

The third level is the (mostly) Out-of-Control Zone. It describes circumstances such as gender or genetics. While you can’t change these factors, you can control the results of them through prevention and mitigation strategies or giving more control to other people such as therapists.

My most important findings are:

Baselines are important: A lot of influences on happiness or depression seem to follow some sort of a logarithmic function. This means that it is more important to have a strong baseline in all of them rather than optimizing one as much as possible. For example, 3x 15 minutes of direct exposure to the sun a week (in the summer), seems to already prevent most of the downsides of too little exposure to the sun. Similarly, intense exercise once or twice a week seems to give you most of the benefits.

Spirals, spirals, spirals: Most of the personal accounts I heard follow a very similar pattern. First, some baseline is a bit worse than it should be but it doesn’t feel drastic enough to act, e.g. some friendships get worse. Then, the situation gets worse and worse over time, but the person feels like they don’t need help (yet). At some point, one or more problems are out of control and other parts of their life come tumbling down as well—a lost friend makes you sad, the sadness keeps you from exercising, the lack of exercise makes you tired which makes you underperform at work and so on. Especially if you have a history of negative spirals getting out of control, the most effective intervention is to implement systems that stop the spiral as soon as possible.

Explore a lot: While some advice might be quite universal, e.g. exercise, sleep, and sun, a lot of other aspects have very high variance between individuals. Especially when it comes to depression, it looks like we don’t have a good causal theory at all. Thus, exploring multiple angles and just trying out a lot is often the most effective strategy, e.g. testing for different chemical imbalances, trying different therapy methods, and trying different medication (for details see Scott Alexander’s website).

Mom was right: As is often the case with rationalist advice, you can either read lots of papers or just listen to your mom and get 90% right. Seriously, “care about your sleep”, “go out into the sun”, “exercise regularly”, “make sure you have good friendships”, “go to a doctor if you have problems”, etc. is advice that sounds oddly familiar. Of course, reading the papers improved my understanding a lot, gave me more context, etc. but the conclusions mostly overlap with what my parents told me anyway.

You have some control: I think especially the “(mostly) out-of-control zone” is sad because it implies that there are important facets of depression that you have no control over. However, I think the core message of the research is a positive one. There are a lot of things you can do to improve your happiness and depression. Even if some type of therapy or medication doesn’t work, another one probably does the job. Even if some parts are out of your control, you can drastically reduce their impact by preparing for them in the right way or intervening before they spiral out of control. This does not imply that only you are responsible for solving them! Systemic solutions for mental health problems likely pay for themselves and should be implemented more.

Framing

Before we get into discussing the three zones, I want to clarify a couple of things about happiness and depression.

Depression is NOT just long sadness

My model of depression from like five years ago was very naive in retrospect. Basically, I assumed that happiness and depression are two ends of the same spectrum and, therefore, depression just describes prolonged episodes of unhappiness. The more I talked to people and read the research, the more I became convinced that this is clearly false. Over time, I learned that the happiness spectrum and depression just describe different phenomena that overlap to some extent.

In this article, I will use the term “happiness (spectrum)” to describe a baseline satisfaction plus (un-)pleasant moments. You could for example be satisfied with your life in general and thus happy, but an annoying interaction could have temporarily reduced your happiness.

Depression on the other hand is an affective disorder/disease and used as an umbrella term for multiple medical conditions, e.g. major depression, persistent depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, or seasonal affective disorder (see here for details). Depression is not orthogonal to the happiness spectrum and negative mood is usually an important condition for it. The most common symptoms of depression are anhedonia, i.e. the inability to feel pleasure, and a loss of drive.

For a great overview on depression, I can recommend this Our World in Data article.

I don’t think it’s possible to fully disentangle the happiness spectrum from depression, but I think it’s important to treat them as different phenomena that correlate rather than part of the same thing. This separation becomes especially important when treating people because “having a bad week” and major depression require completely different solutions.

I found a personal account very helpful to understand depression as an outsider. They described it as if there was “a dense grey veil above everything”. The food didn’t taste like anything anymore, their perception of colors was much less intense and the music was less enjoyable.

As a consequence, this entire post is more like two posts in one. After some considerations, I decided against splitting them into two because many interventions and fundamental principles still overlap substantially between the happiness spectrum and depression.

A more detailed model of whether depression is on the same spectrum as happiness or whether it is categorically different can be found in Scott Alexander’s blog post Ontology Of Psychiatric Conditions: Taxometrics.

A high-level model of happiness

On a high level, there are two drivers to both happiness and depression. The first is a mental component, e.g. through which frame of mind you look at the world, whether you are a positive or negative thinking person, etc. Buddhist monks, for example, reportedly improve their happiness mostly through years of slowly changing their perspective while their material circumstances stay constant. Therefore, I would argue that a mental frame has a significant impact on your happiness and a measurable but smaller effect on the probability and severity of depression compared to other factors such as your circumstances or genes.

This, however, is clearly not the full story. The balance on your bank account, your social relationships, the quality of sleep, etc. usually have a measurable effect on your well-being and you can’t just “think it away” even if you try very hard. Many of these drivers of happiness and depression have physical correlates in your body.

There are broadly four physical correlates of depression:

Transmitters: Certain neurotransmitters have been associated with happiness and depression in many different findings. These include serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. At one point many researchers were convinced that depression was solely an imbalance of neurotransmitters which coined the “chemical imbalance theory of depression”. Today, most people believe that it’s way more complicated, and while neurotransmitters are part of the picture they are not all of it. For a good overview see this SSC post.

Other biomolecules: A lot of different biomarkers have been suggested for major depressive disorder. They include growth factors, cytokines, and other inflammatory markers, oxidative stress markers, endocrine markers, energy balance hormones, and many more (see e.g. this paper).

Heart-rate variability: Interestingly, HRV is negatively correlated with depression severity (see, e.g. this meta-study). I only knew that athletes use HRV as an indicator of restedness, but this comes with the nice side-effect that most sleep tracking devices already measure it.

neuronal activity: researchers have been excited about fMRI studies on depression for a long time. The results, however, are marginal at best. This overview study, for example, suggests that “reverse inference is not possible as MRI scans cannot be used to aid in the diagnosis or treatment planning of patients with [depression]”.

It is important to note that these physical correlates are not necessarily causal for your happiness, sadness, or depression. They could also be the result of the mental component or external circumstances. Thus, my understanding of the literature is that the latest interpretations have shifted away from the “chemical imbalance theory of mood and depression” towards a more complicated picture in which your mental state could be the cause or the effect of a chemical imbalance. Therefore, modern treatments of depression usually include medication and psychotherapy (e.g. CBT) to address both of these two causes.

My personal conclusion from the above is that we should do whatever works to increase our happiness or reduce our depression in a sustainable fashion. If medication works, use it. If therapy/mental frames work, use that. If your condition comes mostly from external circumstances such as pollution, try to change or escape them. I know this sounds quite simple in the abstract but people often still don’t take medication because of stigma or lack of knowledge or avoid therapy for many different reasons.

Much Control Zone

In the much control zone, I categorize decisions that people can make and quickly expect to see results, e.g. in a month. This doesn’t mean that they work for everyone every time but they have a good chance to improve your well-being in expectation.

The Basics

Exercise:

The effects of exercise on your mood are pretty large given that it is such an easy intervention. Some (meta-) studies show correlations between mood and exercise ([1], [2]). This study finds that depression correlates with less exercise, but doesn’t state the causal direction.

Randomized controlled trials show that 8-week physical exercise programs show significant mood boosts in students and the elderly. Physical exercise is also already used successfully as a treatment for depression in hospitals.

It also looks like we have robust evidence that exercise produces serotonin, norepinephrine, BDNF, and dopamine during exercise—all of which are physical correlates of happiness. There are lots of other benefits of regular exercise such as an improved immune system or longevity. Overall, it feels like regular exercise is quite a simple way to increase happiness and I can anecdotally confirm that it worked wonders for me. Also, it doesn’t seem to matter much which sports you do as long as you do it regularly, so just do whatever you enjoy.

Sleep:

Multiple studies show strong correlations between lack of sleep and worse moods (see e.g. [4], [5], [6]).

While it is not super clear whether a worse mood leads to worse sleep or vice versa, attempting to sleep more and at more regular times seems like a cheap shot to increase happiness. In the case of depression, wake therapy (intentional sleep deprivation) has seen large positive effects for some patients. I have written another blogpost on sleep if you want to know more.

Sun and Vitamin D:

This paper suggests that “3.3 Billion DALYs worldwide might result from very low levels of UVR exposure”. While DALYs might not necessarily translate to happiness, the same paper also suggests that serotonin is also affected by exposure to daylight. I would interpret this as soft evidence for increasing sun exposure. Furthermore, there are two papers ([7], [8]) that claim that some forms of depression might be linked to vitamin D deficiencies and thus improvable by exposure to the sun or vitamin D supplementation.

The literature also suggests that three times 15 minutes of exposure to the sun per week is already sufficient to prevent a lot of bad outcomes. This recommendation is under good conditions, e.g. at noon on a summer day without clouds, and should be adapted for worse conditions and seasonality. Additionally, it makes sense to substitute vitamin D, especially during the winter.

There are two things that I would have expected to make a difference where the scientific evidence is either lacking or shows no correlation—namely oxygen and food. I personally found that eating less fatty food and less per meal but more often had small positive effects. Thus, I would have expected small population-wide differences between countries. This, however, does not seem to be the case or has not been sufficiently studied. A higher concentration of CO2 in a room is very damaging for productivity. Therefore, I would have expected that it is also correlated with marginally lower happiness. However, I couldn’t find any evidence for or against this hypothesis.

For all cases above, I would say that it makes sense to invest a bit of time and effort to have a good baseline, e.g. to exercise once or twice a week and make sure your skin gets some sun a couple of times per week. If you are consistently lower than the baseline, e.g. you have a strong vitamin D deficiency, the cost to personal health can be quite high. However, I would not try to obsess with any of them because all gains above the baseline seem to be quite marginal compared to the effort and time required to achieve them. So basically, doing regular outdoor exercise or going for a walk and caring about your sleep seems to be already sufficient for a lot of gains.

Social relationships

Social relationships, or social activities in general, are the most beneficial happiness per cost intervention for most people. There are countless studies that show large positive effects. This study suggests that “social relationships are significant correlates and predictors of happiness” (in children). This one suggests that the quality of relationships is more important to happiness than their quantity. Another one suggests that different types of relationships are better depending on your current happiness levels. But they all agree that friendships are in some way very correlated with happiness. Causality is not super clear, it could also just be that sad people have fewer friends, but from an evolutionary perspective, it does make sense that better relationships are beneficial for survival and thus rewarded with happiness.

For depression, it looks like the effect sizes are comparable or even larger. Lack of perceived social support, social isolation, low quality of friendships and further related social quantities are all strong predictors of depression (see e.g. [9], [10], [11]). This meta-study suggests that “The strongest and most consistent findings were significant protective effects of perceived emotional support, perceived instrumental support, and large, diverse social networks”. The overall conclusion seems to be that bad social relationships are very correlated with depression. Once again, these studies show correlation not causation.

Specifically marriage has measurable positive effects on life satisfaction and well-being. A 17-nation study from 1998 suggests that marriage has a clear positive effect on both partners which is around twice as high as the gain for long-term partnerships without marriage. A 2003 paper shows some causal evidence, i.e. that marriage makes people happy rather than that happy people marry.

Shortly afterward, this paper argues that most happiness gains of marriage occur in the first two years and then people are back to baseline. However, later evidence suggests that this is not the case, and long-term increases in life satisfaction can be causally linked to marriage.

This doesn’t mean you should just marry the next best person since unhappy marriages lead to less happiness than singlehood. Also, most of the results on marriage are 20 years old or older when long-term partnerships outside of marriage were quite uncommon. Thus, I would take the effects with a grain of salt.

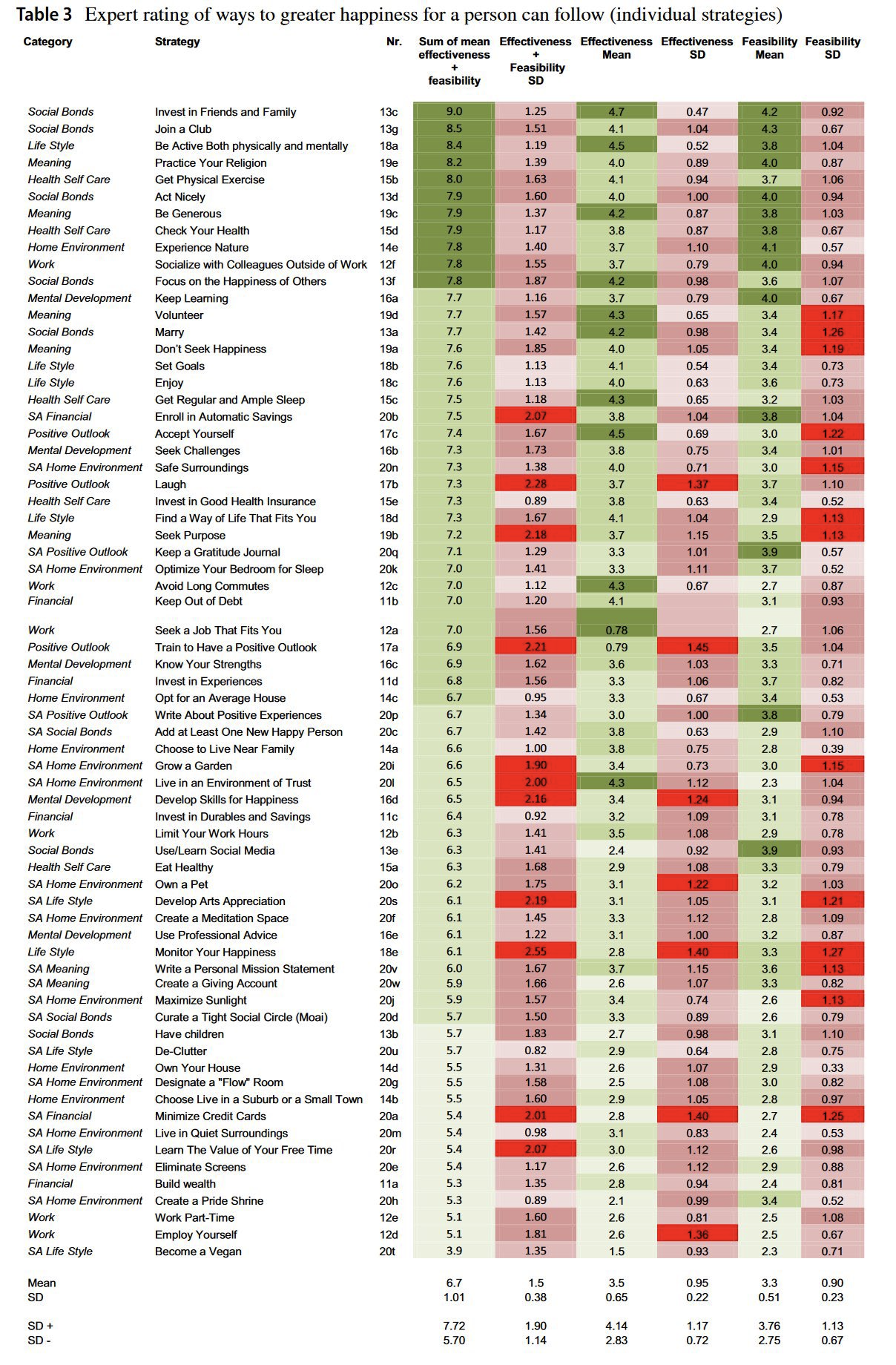

I also found this tweet which references a huge overview study on happiness. The results are very interesting and can broadly be summarised in two figures.

As you can see, on an individual level, most high-ranking actions are related to social relationships in some way.

personal take-away: While I was aware of the direction, I was not aware of the magnitude of the effect of social relationships on happiness and depression. Therefore, I personally will try to prioritize social events and relationships higher in the future.

Medication

There are lots of individual drugs that work wonders for some and might not help others. Our knowledge of which medication helps which person is limited and thus the process involves some trial and error. In general, though, psychiatric medication is way too stigmatized and in comparison to other medical fields extremely cheap and effective. So, in general, it seems like looking for medical treatment options is a very good bet, even if it doesn’t always work.

Everything else I would write about medication would just be a worse version of what Scott Alexander has already written. Thus, I would just recommend you read the relevant sections of this post and this post (might be outdated) if you want to know more about medication for depression.

Mental Frames

While we often have little control over our circumstances, we can still view them through different lenses. This, however, should not be seen as a silver bullet. If you are severely depressed, it’s very unlikely that you can “just think yourself better” if you try really hard. It should rather be seen as little ways that helped me be happier just by changing my perspective on things.

Solution-oriented mindset: My gut reaction to negative news was often to complain or blame it on external factors. While this preserved my sense of purity, it didn’t get me closer to solving the underlying problem and thus made me less happy in the long run. I found that adopting a solution-oriented mindset, e.g. not trying to find blame or fault but just looking for ways to improve the problem, lead to less negative emotions.

Optimism: There is some scientific evidence (see e.g. this paper) and a couple of blog posts (e.g. this one) that suggests that optimism is correlated with happiness (causality is claimed but not shown). From a scientific viewpoint, I would argue that this evidence is insufficient to change your beliefs and some of the papers had shady methodology and looked like motivated reasoning. From a personal anecdotal point of view, I can confirm that I’m happier when I feel like the future is positive rather than negative.

Positive-sum: In a zero-sum mindset one person wins only if another one loses. In a positive-sum mindset, both parties can win. In a zero-sum mindset one thinks “If someone else gets promoted, it could have been me” or “if a friend achieves something, I feel bad because I’m not winning at life”. In a positive-sum mindset, everyone in the company can win if the right people are promoted and you can just be happy for your friends. In general, I feel like a zero-sum mindset can create a lot of “free suffering” since many situations could be positive-sum if you want them to be.

Long-term thinking: Life is often hectic and daily or weekly goals are often not achieved in time. This often feels like one isn’t doing enough or not gaining any ground. A long-term perspective tries to look at longer time frames of e.g. 1 year and focuses on a few set of big goals, e.g. to complete a degree or write a paper. By zooming out the question becomes “did my actions move me closer to my overall goal” or “am I on the correct trajectory” which removes some of the stochasticity of the short-term.

Altruism: There is quite strong evidence that altruism correlates with personal happiness (see e.g. this paper or this one). This includes direct actions, e.g. acts of kindness, and donations. However, the happiness gain does not correlate with the size or effectiveness of the donation—most of the hedonistic effects seem to be gained by the warm glow of giving.

Don’t wait for permission to be happy: For quite some time I held beliefs that I now find rather toxic. They include “The world is unfair. I’m in a better position than many others. Thus, I don’t deserve to be happy, because I didn’t work for it.” and “If I appear too happy, people might think I don’t care about important things”. Now, I think both of them are wrong. If the world is bad you should work towards making it better but this doesn’t require your unhappiness. Also, people think I care about important things based on the way I talk about them and not whether I appear happy or not and furthermore, they usually want me to be happy in the first place. The common theme with these two examples is that I waited for some external force to allow me to be happy. Now I think my fears were unrelated to my happiness and I don’t have to hold my happiness back artificially, as long as my actions are guided towards improving the world.

Some Control Zone

In the some control zone I categorize things that people might or might not have real control over and that usually require a large investment or long time, e.g. you might not be able to switch jobs easily or move to a different place whenever you want to.

Work satisfaction

There are a couple of interesting findings regarding work satisfaction and happiness/depression. Firstly, there is a linear relationship between depression and work performance (see e.g. here), e.g. the more depressed you are the worse your output. Furthermore, work-related stress is correlated with depression in teachers and in nurses. Causality is once again not established but both depression leading to stress and stress leading to depression seem plausible to me.

Regarding solutions, it looks like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) at the workplace has shown mildly positive effects. Additionally, there is evidence that non-treatment is more expensive than treatment. Thus, it looks like there is no trade-off between treatment and productivity but it seems strictly superior to get treatment as early as possible to prevent future costs. Getting help early is a recurring theme and everyone I talked to basically recommends this as much as they can!

My personal conclusions from this are simply that: a) it doesn’t make sense to get a job you don’t enjoy at all and b) if you see work-related symptoms of depression in yourself or your coworkers it makes sense to treat them as early as possible.

Money

The question of whether money does increase happiness is a bit more complicated than I expected. In 1973 Richard A. Easterlin published a paper claiming that absolute wealth does not influence happiness and that only relative wealth, i.e. comparisons to other people in your local society, matter. This phenomenon has been dubbed the Easterlin Paradox.

In 2008, Betsey Stevenson and Justin Wolfers reassessed this question in Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox and came to the conclusion that absolute wealth does matter for happiness even though it has decreasing marginal utility. However, there are other researchers who dispute this (e.g. here). Some even claim that there is a turning point after which more income leads to less happiness on average.

There are still some things we can say with more certainty though. Unconditional cash transfers to Zambia increased happiness quite a bit, so at least below a baseline, absolute wealth does matter. And it depends on what you spend it for: a) spending on others > spending on self, b) spending on experiences > spending on possessions, c) buying ordinary and extraordinary experiences both increase happiness.

My personal takeaways are a) Make sure to have at least a certain baseline of income and wealth, b) money is a very inefficient way to gain happiness compared to other strategies mentioned above and below, and c) It really depends quite heavily on what you use the money for.

Pollution

There is growing evidence for a link between air pollution and depression (see e.g. this report or this article). As always, the study shows correlation and asserts causation. But, at least, they suggest a causal mechanism: dirty air gets through your nose and can reach your brain through the bloodstream. There it might lead to increased inflammation, damage to nerve cells, and changes in stress hormones. All of these are possible candidates for causing bad mental health.

The magnitude of this effect is larger than I expected as “people exposed to an increase of 10 micrograms per cubic meter (µg/m3) in the level of PM2.5 for a year or more had a 10% higher risk of getting depression” where “Levels of PM2.5 in cities range from as high as 114µg/m3 in Delhi, India, to just 6µg/m3 in Ottawa, Canada.”.

Besides air pollution, noise pollution has also been associated with worse mental health. A study by the EU, for example, found that extreme noise annoyance, e.g. next to an airport, correlated with a 5.1 average depression score compared to the 3.5 of the control group (max. score is 27 on a linear scale). Once again, only correlation and no causality was established. I personally find it anecdotally plausible since too much noise drives me crazy.

My personal take-away: consider air- and noise pollution as a factor when relocating. Also, buy noise-canceling headphones—they are great!

(Mostly) Out-of-Control Zone

In the out-of-control zone, I categorize things that you probably can’t change like your genes. However, you might still be able to improve your situation by preventing worst-case outcomes.

Biological determinants

Set-point theory of happiness:

The set-point theory of happiness often referred to as the hedonic treadmill, states that one has a predetermined baseline of subjective happiness (I’m not sure how much this varies between people) and all major positive or negative life events are merely temporary changes to this baseline. According to the theory, after some months everyone would get back to their original baseline.

I was pretty convinced that the hedonic treadmill is real and it has some merit, but there is a lot of scientific evidence showing that the set-point can be changed by quite a lot. Negative life events (e.g. death of a spouse, unemployment, disability) can lead to permanent reductions in the set-point (see this paper). Positive life events such as marriage, friendships, or political involvement can lead to permanent increases in the set-point (see here).

Depending on the definition between 14% and 30% of people have recorded large and permanent changes in their set-point in a large German survey. Furthermore, evidence from China suggests that (un-)employment was a good predictor of a low set-point. My personal read of these studies is that the hedonic treadmill has some merit but should be seen much softer and less deterministic.

Depression and genes:

Genes play a large role in depression. According to this meta-study “the heritability rate for depression is 37% (95% CI: 31%−42%), and data from family studies show a two- to threefold increase in the risk of depression in first-degree offspring of patients with depression”.

We don’t really know which combination of genes is responsible for this behavior and depression and happiness seem to be very polygenic but the fact that inheritance plays such a large role suggests that some forms of depression are partly determined by genes.

Depression and gender:

There is a large gender gap in depression. Women are twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression in their adulthood. The evidence for this finding seems quite robust but it’s not entirely clear why. One factor is biology. Hormone changes during puberty, premenstrual problems, pregnancy, post-pregnancy problems, and menopause have all been linked to higher likelihoods of depression (see here).

This would fall in line with the chemical imbalance theory of depression. However, there are probably social factors as well. Due to social expectations and stereotypes, women might be more likely to admit depression and accept treatment than men. This is hard to measure but would fall in line with comparable results in e.g. chronic pain. Another hypothesis is that women might be more likely to be depressed due to worse socio-economic circumstances and society-wide power imbalances. I can definitely see how a woman in a patriarchal society has an increased risk of depression.

Depression and Age:

The likelihood of depression changes over your lifetime. The study ‘Age and Depression’ from 1992 claims that it reaches its lowest levels at age 45 and peaks at 80. A Norwegian study from 2003 claims that depression basically increases with age with no drops in between.

So they agree that being very old increases your chance of depression but disagree about the trajectory during your working age. On the other hand, the age at onset of major depression seems to peak at 28, so I’m not sure what to make of this. Unfortunately, most of these studies are quite old and I would therefore like to see more recent findings on the relationship between age and depression.

My personal take-away: a) the last three are really sad; b) Don’t judge people for their depression. They plausibly are just victims of biology; c) embrace transhumanism!

Fail-Safe Mechanisms

In the 80K podcast episode on depression and anxiety, Howie says that he recommends establishing fail-safe mechanisms for depressive episodes, especially if you have a history of depression or other mental health problems. A fail-safe mechanism might be established through the following guidelines.

The goal is to make decisions while you still can. During bad states of mental health, even simple tasks can seem insurmountable. Thus, the goal is to create a strategy that requires as little action as possible during the bad episodes and shift all the work to the good episodes.

Make it easy: Like really easy. Reduce the workload to pressing a button or saying one word. Possible strategies include

pre-writing an e-mail along the lines of “I’m in a bad state right now. I won’t be able to do work for a bit. I’ll be back when I’m better”. So that you just have to press send once you are in a bad state.

Saving all important phone numbers as shortcuts, e.g. you could add the string “(help)” to the contact of your best friend, your parents, and the suicide hotline in your phone. So when you’re in bad shape, you just have to type “(help)” in your phone and call the first number that pops up.

You can have opt-out systems, where a trusted person expects you to write “I’m fine” every couple of days. Once you don’t write it, they know you are in a bad shape, call you to verify, and can contact your friends, employer, and therapist to make sure the burden is not on you.

Talk to people about it. Just tell your friends or employer that there might be bad times and it’s not their fault if you don’t write back for a bit. It lifts the mental burden of “being a bad friend/employee a bit” because they already know beforehand.

Work with someone you trust: With all strategies, it makes sense to work with someone you trust and can count on if the bad episode hits.

While the above are individual solutions for some, many people in society either don’t have access to them, e.g. because their employer doesn’t give a shit, their surroundings have stereotypes around mental health, or they simply don’t have friends they trust enough. Furthermore, while you might trust your friends or family, they are likely not trained for such a situation.

So I would certainly welcome it if these tasks could partly be solved by professional institutions. This might include practical advice about mental health in schools, mental health hotlines, or professional systems that simplify the entire process in bad times.

Conclusions

I have moved the conclusions to the top because most people don’t read until here.

One last note

I would like to thank Domi and Jonathan for their in-depth feedback and expertise.

If you want to get informed about new posts you can follow me on Twitter or subscribe to my mailing list.

If you have any feedback regarding anything (i.e. layout or opinions) please tell me in a constructive manner via your preferred means of communication.

If the field of psychiatric diagnoses wasn’t focused on being quite pseudoscientific in the way it approaches diagnostics (see the process that creates the DSM) I would expect that we would find statements that are similar to those cancer researchers who say “Cancer isn’t an illness but many”.

Depression caused by traumatic brain injury is likely different in nature then a lot of other depression.

Not getting angry is not one of the official diagnostic criteria for depression.

Depression is not something you can have a single day. You can be very unhappy for a single day but that doesn’t mean depression.

Can you clarify? Are you saying that you are only happy while actively procreating or increasing your children/relatives’ chance of precreation?

I think winning at sports is more of a thing that lead to our ancestors increasing their chances of procreation. Would you feel as happy about your relatives becoming sperm or egg donors?

To me, executing adaptations that probably made my ancestors increase their chances of procreation does make me happier (flirting successfully with people, feeling high-status, eating good food, etc), but not the things that actually maximize my current inclusive fitness. Otherwise, I would be really happy about the thought of becoming a sperm donor! You might be interested in this post about executing adaptations.

If you had the choice of not having sex but get to have your donated sperm fertilized vs having sex but never be able to have your own biological children, what would you choose?